Home » Jazz Articles » Musings of a Jazz Piano Teacher » Working with jazz singers

Working with jazz singers

In some respects comping is the same whether behind an instrumentalist or a singer. However, in other respects it is totally different. Let's start with the similarities.

When comping, the spotlight is on the soloist, and it is our job as accompanist to both support them and make them sound good. The first assessment that needs to be made is their level of experience. At one end of the spectrum, if the soloist has limited experience, they may require plenty of rhythmic and melodic help. For example, they may need to hear the first beat of every bar. If they are playing or singing a melody, then the melody, or at least its outline, may need to be stated clearly.

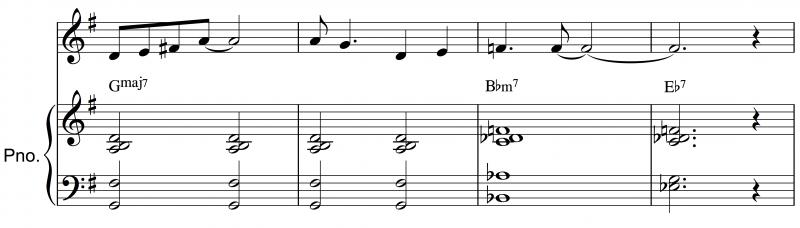

In the two following examples I'm comping bars 1—4 of Out Of Nowhere.

In the first illustration my comp is on beats 1 and 3.

Although this provides a clear indication of downbeats, it provides no melodic or rhythmic support to the melody.

The next illustration meets both these requirements by placing the melody note at the top of chords and tracing its rhythmic pattern.

Of course, one can be far freer and more interactive with the soloist, but this is relative to how much or little support they require.

Comping behind a jazz singer

I have to confess that there was a time when I sometimes had issues with the phrase 'jazz singer.' This was because I often found myself accompanying singers who were more cabaret than jazz, but performed standards in a 'jazzy' fashion simply by dragging the beat. I have since come to work with some wonderful singers that are every bit as skillful as any jazz instrumentalist.

So this article is not a disguised tirade against singers, but rather an indication of how I help learning jazz pianists to work with them.

In an ideal world the singer possesses a sound knowledge of music, has equal status with other band members and is considered to be a musician whose instrument happens to be the voice.

The reality is that some vocalists have a minimal grasp of music for practical purposes but are expected to act as the bandleader: stating the keys, tempo and arrangement to band members. This situation often stems from the singer being required to front the band as a focal point.

Over the years I have advised vocalists as to their role and duties within a band situation. Nowadays, because my main focus is working with pianists, I advise my students as follows.

Here are the issues that are certain to come up:

Choice of key

Do not assume that the key in your songbook will be a suitable vocal key. The singer must be able to hit the top note of the song without strain.

I recommend the following process:

1. Find a section of the song that contains the highest note.

2. Test this section with your singer by transposing the section down until the vocalist feels comfortable.

3. Double-check this new key by locating the section with the lowest note and ensuring the song is still in a singable range.

Many female singers choose to stay within their lower range when singing jazz, but I always encourage vocalists to explore the upper register. Listen to Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald for inspiration.

Starting the song

Here are five options.

1. Count in.

2. The pianist plays the starting note (known as the bell note). The singer and band then start simultaneously, without any need for a count-in.

3. The pianist provides a broken chord (arpeggio). This should be the dominant 7, possibly containing a raised 5th. If the song is in G major, this augmented chord would be D7(#5).

4. The last 4 bars of the A or B section can be played as an intro. This will usually contain a I—VI—II—V turnaround. However, if the song is up-tempo, 8 bars might be preferable.

5. Many standards, particularly ballads, begin with a verse or introduction. This is often played out of tempo (colla voce). Your role, therefore, is to follow the singer until the song falls into tempo (or falls apart!) on beat 1 of the chorus. Once again, it should be the singer's responsibility to 'bring the band in,' but the leader or drummer can help out here.

* Seek out Tony Bennett's version of All The Things You Are to hear its verse. Incidentally, if you have any doubts about Bennett's credentials as a jazz singer, listen to the two albums he made with Bill Evans.

Ending the song

This is the outro. Whether the song comes to a dead stop or slows down, it is again the singer's responsibility to convey their intention to the band. To indicate an approaching tag (extended ending), the singer might revolve a finger clockwise.

Arrangement

A typical arrangement might be as follows:

1. Verse—sung. 2. Head—sung. 3. Solos. 4. Swap 4s. 5. Head—sung.

The singer may choose to return to the final head at section B. This should be conveyed to the band towards the end of the final solo.

The singer may also wish to take a solo in the form of a scat vocal.

Back to the head

The final soloist (particularly the drummer) should hand over to the singer with precision, rather than with a wild flurry of notes (or beats).

In the end it is the combination of preparation and effective communication that makes for a good musical relationship between the pianist and singer. Once this is in place, we have enabled the singer to perform with ease and confidence.

< Previous

Second Springtime

Next >

Poor Butterfly

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.