Home » Jazz Articles » Out and About: The Super Fans » Meet John Reilly

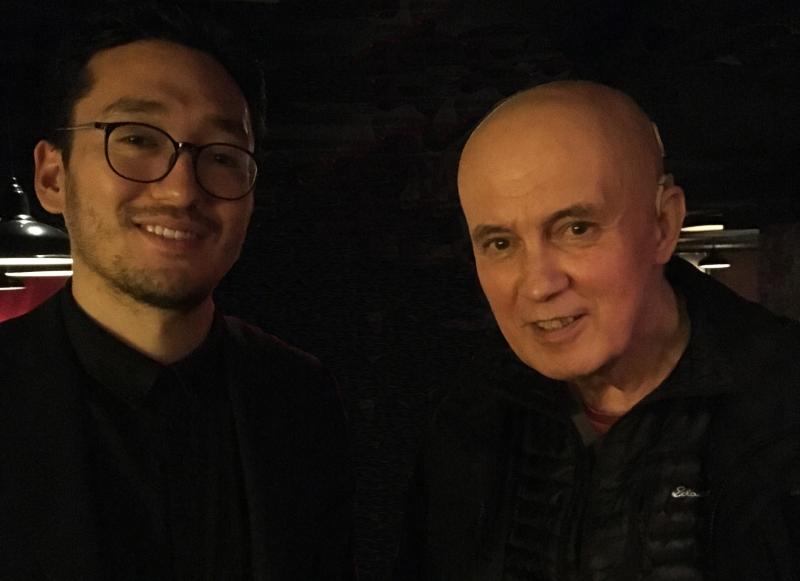

Meet John Reilly

One night I was there when Slide Hampton really went over the top. That really taught me that sometimes these things can happen. Everybody has those nights and I’ve heard them and they are special. If you go out a lot you encounter these things.

—John Reilly

What is your earliest memory of music?

When I was about three I had a kid's record about firemen. The words were, "Fire, fire, fire, raging all about, here come the firemen to put the fire out." That's the earliest thing I remember. Beyond that, I remember hearing country music at my aunt's house. And my mother was big on Frank Sinatra; she was one of those girls who would go to the Paramount Theater early in the morning and get on the line to watch his show over and over again. And my father, I know he went for Bing Crosby.

How old were you when you got your first record?

There was a farmer's market in a former airplane hanger on Staten Island, and one day, when I was about 14 or 15, I went in and this vendor was playing the same record over and over again. I remember saying, "What's that music? What's that playing?" It was the Smokey Robinson record, "Shop Around," with the The Funk Brothers, and I bought it. It really lit me up what that rhythm section was able to do, which was not what was going on in any other music at that time. I bought it out of my allowance. It was probably about 35 cents for a single in those days. I played it as much as I could when I got home. I don't think my parents went for it.

The first real jazz records I had were Miles Davis, Steamin', a Coleman Hawkins record just called Coleman Hawkins, Sonny Rollins' St. Thomas, and John Coltrane's Traneing In. I bought them at Sam Goody's, where they sold cheap records in the discount bin. They were probably two or three dollars. A little later, Riverside Records was in receivership, not very long after they started, really, and they had that great catalogue which they'd recorded in a very short time frame. So what they did to make money was they went to a cheap presser and dumped hundreds, maybe thousands of them on a record store around 42nd and Seventh Avenue, where they were on sale for $1.77. I remember that price tag. I got quite a few of those.

How did you get into jazz?

First, all those TV variety shows. The Ed Sullivan Show, which was every Sunday, had the Count Basie Orchestra. He used to open up his numbers with a little solo before the band would come in, and I was entranced. I also remember Louis Armstrong. I wasn't passionate back then, but I knew I was paying attention when [jazz] people came on. That led to me to turning on the radio, and one of the first jazz shows I got into was on WLIB with Billy Taylor. That's how it goes. Now it's very rich. You have WBGO. I don't know if it's rich in the rest of the country, but around here BGO gives everybody an education. And it's going 24 hours a day. It wasn't like that then. You had to work at it. There were magazines, too. The Metropole and Downbeat, and that would lead you to books. There always were the books. You'd get some of them in the library.

There was also the famous Symphony Sid [deejay Sid Torin, who is credited with introducing bebop to the masses.] For all his fame, he was not a radio educator. He may have been good at one time, but I heard them play a tape of the station ID followed by Lester Young's "Jumpin' with Symphony Sid" over and over again for hours late at night, with no other jazz records. This happened many times when I tuned in.

It was AM radio, which in those days didn't work very well in during the day, so you had to listen at night. That led me to the black radio stations in Newark. When I went to college a few years later in North Carolina, they used to blast the Chicago stations at night. It was almost all you could listen to. That was rhythm and blues, though, not jazz.

What was the first jazz concert you attended?

It was close to my 18th birthday. I came home from college and my parents took me to the famous gig that Sonny Rollins did, after his years of rehearsing on the Williamsburg Bridge. It was at the Jazz Gallery [Ed note: Not to be confused with the current Jazz Gallery, a separate venue], a theater on St. Mark's Square where they did the Charlie Brown Show for years. I was crazy about Sonny Rollins. They knew that I had made the switch to jazz, and were probably glad I had got away from those doo wop singers. Because you didn't have headphones in those days. A few days later I had to get a bus back to North Carolina at 12.30 a.m., so before the bus came that night my parents took me to the old Birdland. It was a Monday night and there was a jam. Oliver Nelson and Frank Strozier were there, I remember.

How long have you been going out to hear live music?

Over 50 years. The first things I remember going out to were when the rock and roll disc jockeys had these shows in the big theaters, like the Paramount. There were nice big old palaces. Most of the time they had people like Jackie Wilson or Stan the Man Taylor leading the bands. Lots of different doo wop groups. Jackie Wilson was a dynamo on stage. And he had jazz guys in there.

How often do you go out to hear live music?

Well, now I'm in a situation where I don't have to work nights anymore, and I have the time and the money to go out somewhere between three and seven times a week. Sometimes I do seven. Probably more often three to five.

What is it about live music that makes it so special for you?

The ebb and flow of inspiration. Often better than the records. It's heart and soul. You've got people who are really working hard to create the emotional communication thing. The people who are real good, that's what they can do. That's what they did do. It's the emotional charge and you can depend on it. I've seen times where people want to talk and the energy goes out of the room. The musicians play competently then, but you're not getting the jazz thing. But by and large you can rely on them. They're selling it for real!

What are the elements of an amazing concert?

When you can tell that they've played something that's really exceptional and you know it and they know it. It's partly the emotion but it's also the intellect because sometimes you can see the musicians thinking, "What the heck did I do?" They've surprised themselves. One night I was there when Slide Hampton really went over the top. That really taught me that sometimes these things can happen. Everybody has those nights and I've heard them, and they are special. If you go out a lot you encounter these things.

If you could go back in time and hear one of the jazz legends perform live, who would it be?

I missed Charlie Parker. I was too little a kid. But I remember my parents took me into Manhattan after he died. In those days I don't remember graffiti—that was a thing of the '60s and later. But I can remember seeing on buildings, "Bird lives," and I said, "What's that? What's this 'Bird lives' thing?" I didn't know who the heck Bird was then, but I remember that graffiti. But I guess if I could go back and hear anybody I'd want to hear Art Tatum because he was totally unique. He learned how to play by copying piano roll recordings that his mother brought home. But he didn't know that the piano rolls he had were for four hands, so he figured out how to play four-handed piano with two—that's why he could do all that stuff! That's Jon Hendricks' story. That's what Art Tatum told him.

Which club are you most regularly to be found at?

Smalls Jazz Club (it's a little small but I love it), Mezzrow, The Jazz Gallery, The Jazz Standard, The Stone, The 55 Bar, the places you know of in New York. I'm not crazy about Birdland because it's a big barn, and any place that's too big, the sound kind of bounces around for me, because I have hearing devices on. So boomy stuff is a big limitation for me. I like the small rooms. Sweet Basil's was kind of boomy too, but they were such good bookers, I went anyway.

Which clubs did you go to all the time back in the day?

When I got out of school and could first go to clubs, I went to the Village Vanguard a little. It was very different then. Max had these bar staff who would try to make you drink a lot, and it was full of smoke. The smoke made me sick, so I moved on and stayed away for awhile. One of the first places I went to regularly was Pookie's Pub, down on Hudson St. When Elvin Jones left Coltrane, he went in there and played several nights a week for months at a time. He had Joe Farrell and later Frank Foster. He had Wilbur Ware, he had Billy Greene. But you could sit right near to Elvin and listen to him weave the magic, so I went there a lot. When he left there they tried it with Charles Mingus, but he just didn't draw like that. Elvin had the magic; he could have been in there by himself and you would have watched him for three hours.

Then, later on, because of the Village Voice, I'd try something else. I became one of the people that would go to Slug's Saloon. I saw Charnett Moffett and the family band there. They used to play on Sundays. Jimmy Heath and Art Farmer. Chick Corea. Art Blakey. A lot of hard bop. I remember Wayne Shorter used to be playing in there with McCoy Tyner and they couldn't get him to stop playing. It would be 3 a.m., and New York cabaret laws said you had to stop, but he wouldn't. He just wasn't finished.

Did you see Lee Morgan?

I saw lots of Lee Morgan. He played great! I used to sit way in the back at Slugs. There was a bar on the left, and an area with counters and stools to right , and tables down to the stage from the end of the bar. So I'd be sitting over to the right, and on the breaks Lee Morgan would come to the bar. It looked very strange to me because he always had this crowd of women, only women, all around him, and then the famous Helen [Morgan] would approach, and the women would break for her. He would look very arrogant, surrounded by these women, but they'd break for her. It looked very odd. Fortunately, I wasn't in the club the night of the famous murder.

Is there a club that's no longer here that you miss the most?

People have forgotten Kenny Burrell once had a club called Guitar. Just guitar and bass was not an established thing in the city until Kenny Burrell started that with this club. I don't think there were ever drums in there that I recall. He had great people. It was the only time I got to see Skeeter Best. Chuck Wayne was there. Kenny was there in the beginning. The Jim Hall and Ron Carter thing started there—Kenny put that together. I also miss Visiones. That was terrific, especially John Hicks there. Cobi Narita's productions on Lafayette Street. Mark Morganelli's Jazz Forum on Cooper Square and on the 5th floor of Bleecker Street and Broadway. So many places that aren't here now.

Do you have a favorite club now?

The best club in terms of sound—and something about the atmosphere brings up the performance level, I think—is the Village Vanguard. Lorraine's Vanguard. Not Max's. Lorraine's Vanguard, I think, is tremendous. Max's was almost as good but I think he was screwing it up with the tough waiters and bartenders always selling you booze. And the smoking, which was awful.

Vinyl, CDs, MP3s, or streaming?

If I am reading about something or I see a listing, I will go to YouTube to see what they're like. I don't use it as a way to listen to music. It just doesn't have the passion of even records, and certainly not of sitting there in that audience in front of it. I have crates full of LPs, even though I don't play them that much nowadays. Between working and going out, I don't listen at home. I listen in the car when I'm traveling, but otherwise I like to be there in the audience.

If you were a professional musician, which instrument would you play?

I had the hearing thing so I knew there could be some limitations with intonation. When I was in college, one year in my dorm there was a guy who became a professional drummer; he gave me some drumsticks and it gave me an outlet. I had a nervous habit of playing the drumsticks on my leg. Or maybe I'd like vibes, or tenor sax or trumpet—they sing my lines in my head. But people always pushed me away from studying because of the hearing thing.

What do you think keeps jazz alive?

The musicians. They're the ones that get out there and hope that the people come and catch them. These guys are often terribly underpaid. It's them. They keep the business going. It's not going to die because there's always going to be people who want to work. And they work for too little, but that's the nature of the business.

Finish this sentence: Life without music would be...

Gee. Not very good, right? Not the way I've been living. I don't know what else I would do. It's easier for me to perceive the music than the words sometimes with the hearing thing. People talk fast and things get by you. It takes a while to pick up on what's going on. But music gets through. It's real. It's right there.

< Previous

Taking Direction

Comments

Tags

Out and About: The Super Fans

Tessa Souter and Andrea Wolper

frank sinatra

Bing Crosby

Smokey Robinson and the Miracles

Funk Brothers

Miles Davis

Coleman Hawkins

Sonny Rollins

John Coltrane

Count Basie Orchestra

Louis Armstrong

Billy Taylor

Lester Young

Birdland

Oliver Nelson

Frank Strozier

Charlie Parker

Jon Hendricks

Art Tatum

Smalls Jazz Club

Mezzrow

The Jazz Gallery

The Jazz Standard

the Stone

The 55 Bar

Village Vanguard

Elvin Jones

Joe Farrell

Frank Foster

WIlbur Ware

Charles Mingus

Charnett Moffett

Jimmy Heath

Art Farmer

Chick Corea

Art Blakey

Wayne Shorter

McCoy Tyner

lee morgan

Kenny Burrell

Skeeter Best

Chuck Wayne

Jim Hall

Ron Carter

John Hicks

Mark Morganelli

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.