Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Komeda: A Private Life In Jazz

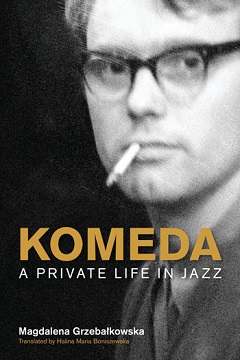

Komeda: A Private Life In Jazz

Komeda: A Private Life In Jazz

Komeda: A Private Life In Jazz Magdalena Grzebałkowska

456 Pages

ISBN: 978 1 78179 945 1

Equinox Publishing

2020

That it has taken over fifty years for the first English-language biography of Krzysztof Komeda to appear reflects the pianist/composer's underground status outside his native Poland. Yet no history of European jazz would be complete without mention of this modernizing figure, whose career burned briefly but brightly from 1956, when he launched his modern jazz sextet, until 1969, when he died, a rising film composer, in tragic circumstances in Los Angeles. Award-winning journalist and author Magdalena Grzebałkowska's book was published in Polish in 2018, but thanks to Equinox Publishing and a first-rate translation by Halina Maria Boniszewska, a rounded picture of Komeda emerges for international readership that places his achievements in context.

After the opening chapter, which details the heady atmosphere surrounding the 1956 Sopot Jazz Festival and the performance of Komeda's sextet there, the chapter titles are headed "Thirty-eight years to go," "ten years to go," "Seventeen days to go" etcetera, as the author measures the sands of time remaining in Komeda's personal hourglass. It is just one example of the author's engaging style, which reads, in many ways, like a film script. Certainly, Komeda's life and times would translate very well into a big-screen biopic.

Born Krzysztof Trzciński on April 27, 1931, in Poznań, to Mieczyslaw Trzciński—a bank clerk—and Zenobia Trzciński—who ran a wool shop— Krzysztof later chose the name Komeda, for reasons that are not made entirely clear. Aping their American counterparts, Polish jazz musicians frequently adopted hipster nicknames, though in Trzciński's case it may have had more to do with distancing his jazz persona from his—short-lived—medical career.

Taught piano by his mother from the age of four, Komeda contracted polio at eight, resulting in a permanent limp, which likely contributed to his quiet, undemonstrative character. In September 1939, the family returned from the coastal holiday village of Chałupy to find that a German bomb had destroyed their apartment block— an air-raid that took 245 lives. Refugees, the Trzciński family set off for Warsaw, but bomb-damaged tracks forced them back, by foot, to Poznań. Except Poznań was now Posen, renamed by the German occupiers. Life was severely restricted. Poles were forbidden from even sitting on park benches and "food rations are determined by 'purity' of their race."

The Trzciński family moved to Czestochowa where they found some stability, though the end of the war brought Soviet tanks and another brutal occupation. Komeda's personal battles, the author relates, came later on. First, in choosing between a career as a doctor or a professional jazz musician, ("I wanted to hide my performances from my colleagues; to have the status of doctor mattered to me very much at that time.") and later still, between scuffling for a living playing jazz and reaping the financial benefits as a film composer in Hollywood. The first dilemma was not an easy one to resolve and Komeda would later express some regret at having abandoned a career in medicine. The second life-changing choice appears to have been less problematic.

Grzebałkowska has left no stone unturned in her efforts to discover Komeda the man and Komeda the artist. In addition to excavating existing publications, Polish national archives and the specialist jazz journals of the time—and as interviews of substance with Komeda were few—the author builds a picture of her subject through those connected to him personally and professionally—eighty-two interviewees in total. Her original wish-list had been 156, which doubtless would likely have added significantly to the book's 456 pages. As it is, her forensic detail can seem, if not quite superfluous, then a little too fleshy at times.

For example, Grzebałkowska pays a lot of attention to Komeda's wife and manager, Zofia, a former partisan who seemed to rub most people the wrong way. An ever-present figure in the early stages of Komeda's career, Zofia the manager effectively became redundant when her husband all but abandoned jazz for film score composing. Tales of her temper tantrums, headbutting and excessive drinking may explain the fissures in the Komeda's relationship but grow repetitive after a while. Still, you can't have your cake and eat it, and the author's attention to minutiae in general creates a vivid picture of the vodka-fuelled Communist times in which Komeda lived and worked, and of the changing fortunes of jazz in post-Stalin Poland.

When the 1956 Sopot Jazz festival opened its gates to somewhere between 30,000 and 60,000 punters—with 200 Polish journalists in tow—traditional or 'hot jazz' was all the rage among jazz fans isolated behind the Iron Curtain. Komeda's music, however, embraced a cooler modernity typified by his influences—The Modern Jazz Quartet and Gerry Mulligan. Fans and critics alike were divided, with Komeda's detractors bored and dismissive because they could not dance to his classically filtered cool jazz, while his champions heralded the arrival of a game-changing contemporary artist.

Jazz, like Polish society itself, was in flux, its fortunes waning as rock 'n' roll seduced Polish youth in the 1960s. Interviewed in 1966, Komeda was asked if he thought the drop in jazz's fortunes was normal: "Absolutely normal," he responded. "What was abnormal was the huge interest in jazz at the end of the 1950s."

Though Komeda's groups, which included at various times Tomasz Stańko, Michal Urbaniak, Janusz Muniak, Zbigniew Namyslowski, Jan Wroblweski, Jerzy Milian, Jan Zybler, Maciej Suzin and Urszula Dudziak, amongst others, recorded relatively few studio albums, they were feted internationally, with invitations to perform in the German Democratic Republic, Russia, France, Sweden, Denmark and the Czech Republic—all chronicled by Grzebałkowska with the dogged persistence of a journalist who understands that many little pieces make for a grand mosaic.

As a pianist, Komeda was no virtuoso, his real strengths residing in his musical conception and in his ability to coax new language from the musicians he chose to work with, like saxophonist/organist Wojciech Karolak: "His piano playing was a bit messy, to be honest; I didn't particularly like it. But he had an exceptional gift for inventing simple, extraordinary things." Stanko noted: "He gave us a lot of freedom even though he had the notes written down. That's unusual for jazz. But that was his great strength."

At the end of 1965 Komeda recorded his most famous album, Astigmatic (Muza), which was to be his last jazz album. For some years Komeda had been composing film soundtracks, and his early student collaborations with a young Roman Polanski were blossoming into a fully-fledged career. For his soundtrack to Jerzy Skolimowski's award-winning film Le Départ (1967) Komeda had recruited the likes of Don Cherry, Gato Barbieri and Philip Catherine.

Jazz, however, once Komeda's great passion, no longer seemed to hold much allure, and in 1967 he left Poland for Los Angeles, where he enjoyed considerable success composing film scores, notably for Polanski's Rosemary's Baby (1968). "It wasn't for the first time that a film of mine took on an extra dimension thanks to the wonderful, richly inventive music of my friend Komeda," Polanski recalled.

The details of Komeda's death are contested and murky, but that he fell at his home and suffered what later proved to be a fatal head injury are the bare bones of the truth. We may never know, as all the alleged witnesses that night are long since dead. Two of those, Wojciech Frykowski and Gibby Folger would meet a grislier death a few months later, in Polanski's villa, at the hands of Charles Manson's sect. The author was perhaps clutching at straws when, in 2016, she called at Komeda's former LA villa, and at the neighbouring houses, in the hope of finding a witness to Komeda and that night. Not surprisingly, she came away empty-handed, though it is symptomatic of the lengths she went to in order to better know Komeda.

Perhaps an introductory essay outlining Komeda's enduring importance as a jazz artist, particularly in Poland, would have been helpful for those readers less familiar with his music. A definitive discography would not have gone amiss either. These minor complaints, however, do not detract from Grzebałkowska's thorough and wit-laced examination of Komeda. A highly readable tome that will likely serve as the main reference on Komeda for many years to come.

< Previous

20 Seattle Jazz Musicians You Should ...

Next >

Balcony Lullabies

Comments

Tags

Book Review

Krzysztof Komeda

Ian Patterson

Equinox Publishing

Modern Jazz Quartet

Gerry Mulligan

tomasz stanko

Michal Urbaniak

Janusz Muniak

Zbigniew Namyslowski

Jan Wroblweski

Jerzy Milian

Jan Zybler

Maciej Suzin

Urszula Dudziak

Wojciech Karolak

Don Cherry

Gato Barbieri

Philip Catherine

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.