Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Indian Sun: The Life And Music Of Ravi Shankar

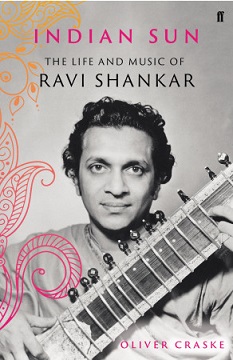

Indian Sun: The Life And Music Of Ravi Shankar

Indian Sun: The Life And Music Of Ravi Shankar

Indian Sun: The Life And Music Of Ravi Shankar Oliver Craske

658 Pages

ISBN: 978-0-571-35085-8

Faber & Faber

2020

The title of Oliver Craske's fascinating and exhaustively researched biography of Ravi Shankar, one of the greatest artists of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, is something of a misnomer, for music was the Indian sitarist and composer's life—the sun around which he revolved. It ran in his veins, in his heart, and in his ever-restless mind. Those who knew Shankar well describe his fingers playing the sitar as he dreamt. He would habitually play rhythm games at the dining table, and when he wasn't practising, composing, or performing, all of which he did into his nineties, he was teaching—for free. For Shankar, it seems, there was no division between music and life.

Unless, of course, you consider Shankar's innumerable romances, which could amount to a biography in themselves. Shankar's appetites, or rather his addictions, the author relates, were the source of both his greatness as an artist and of his weakness and folly as a man.

Craske, who packs a remarkable amount of detail into a relatively concise book, knew Shankar for the final eighteen years of his life, having worked closely with the musician on his autobiography, Raga Mala (Genesis Publications, 1997). The trust that the London-based author earned from Shankar's family, his close friends and collaborators is clear from the confessional intimacy of many of his interviewees, and from the access he gained to Shankar's archives. The result is a warts-and-all—though ultimately sympathetic—portrait of a deeply spiritual, and equally troubled individual, whose main goal in life was the preservation of Indian classical music.

Celebrated in the West by classical composers, jazz, folk and rock musicians, counter-culture hippies and avant-garde experimentalists alike, Shankar influenced everyone from John Coltrane, Jeff Beck and George Harrison to John McLaughlin, Phillip Glass, Talvin Singh and Nitin Sawhney. He was criticized at home for allegedly diluting the tradition for the comfort of Western audiences by playing shortened recitals (two and a half hours as opposed to the five or six-hour marathons that were his norm in India), and for his cross-over experiments with Western classical orchestras. Yet in whatever direction Shankar's muse led him—he embraced fusion and World Music decades before these terms gained common currency—he was a tireless traditionalist at heart, with the raga form at the center of everything.

Born to a landowning Bengali Brahmin family in Benares, on April 7, 1920, Robindra Shankar Chowdhury didn't take the name Ravi until he was twenty, by which time he had already seen a significant slice of the world as a dancer in his brother Uday's ground-breaking troupe. Craske relates a great anecdote whereby, decades later, George Harrison is driving Shankar into London, with music playing on the car stereo. 'Who's that?' inquires Shankar. 'Oh, it's Cab Calloway, you won't know him,' says Harrison. 'Oh yes, I saw him at the Cotton Club around 1933,' comes Shankar's reply.

Cosmopolitan and worldly from an early age, Shankar was equally at home during his relentless tours of Europe or America as he was in India. On stage, Shankar dressed traditionally, but offstage, as The Beatles led the hippies in donning Indian attire, he travelled in a suit. He hobnobbed with admirers Benjamin Britten and Imogen Holst, and recorded with Yehudi Menuhin, while his concerts attracted royalty and heads of states. He played both the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock, though was never comfortable with the embrace of the drug-taking counterculture and was utterly horrified at the sight of Jimi Hendrix destroying his guitar at Monterey—a musician's instrument being sacred to the sitarist.

A constant theme in these pages is Shankar's dedication to his craft. For six-and-a-half years from 1937 to 1944, he studied between eight and sixteen hours a day under the tutelage of sarod maestro Alludin Khan. Not for nothing was Shankar revered globally for his virtuosity. Yet for Shankar, the essence of Indian classical music was something other. Virtuosity, Shankar reasoned, was to be found in every musical culture, whereas the unique beauty of Indian classical music lay in its meditative and spiritual qualities. Critical of the often chatty, informal attitude of Indian audiences, he generally preferred the concert-hall sobriety and attentiveness of Western audiences. Every concert, it seems, was treated like a religious offering.

In his lifelong mission to introduce Indian classical music to the West, Shankar wrote three East-West concertos and an opera based on raga forms. His boldest experiments, perhaps inevitably, met with mixed reviews. André Previn, Craske recounts with an admirable sense of balance, dismissed Shankar's first sitar concerto, recorded in 1971, as "absolute, total utter shit..." though Capitol Records was more than pleased with its healthy sales. Shankar's second concerto, premiered in 1981, was favourably received in the West, but less so in India. As the author notes, Shankar's "fervent drive to be faithful to Indian music in the face of accusations that he was doing the opposite was to cause him more anguish than anything else in his professional life."

In his personal life Shankar carried within him a much deeper anguish. Incredibly, he didn't meet his father, a politician, barrister, international lecturer, and composer, until he was eight. At the tender age of seven Shankar was raped by a close relative and would be sexually abused as a child once again whilst on tour in Paris. He kept these traumatic events bottled up inside him until the latter years of his life. The death of his beloved eighteen-year-old brother Bhupendra also affected Shankar badly, as did his parting from his mother when he was fifteen.

These traumas, the author posits, help explain Shankar's constant feelings of loneliness, his one-time suicidal thoughts and spiritual yearning, his workaholic character, and his obsession with music. The gruelling touring schedules—eight decades of pin-balling around the world—beggar belief. No wonder that in his autobiography he wrote, "Everything was a blur." A common observance by those closest to Shankar is of his delightfully playful, child-like nature, as though he clung onto the sort of childhood he rarely had, or could not move on from.

Certainly, Shankar's constant need for loving devotion and affection, no matter who he hurt in the process, and his difficulty in committing, whether to the music schools he founded, or to his two children born of extra-marital affairs, suggest a man always on the run, and one always striving for something just out of reach. Towards the end of his life, however, and thanks to the stabilizing effect of his second wife Sukanya, Shankar appears to have found a sense of emotional resolution.

Shankar's musical and cultural legacy remains profound, and not just in the West. As Craske notes, Shankar led the way in creating a mass market for Indian classical music in India, through his film scores, theatrical productions and radio broadcasts, in a tumultuous period of Indian history where the shackles of British colonialism were cast aside and a nation, amidst much bloodshed, was born anew. Shankar's departures or arrivals at India's airports were considered news worthy by the national press, and, largely thanks to Shankar's revered status, the honorific terms Pandit and Ustad—once the preserve of scholars—were extended to musicians.

Shankar embraced the music of both northern and southern India and educated his Indian audiences in the subtleties and depths of Indian classical music. He brought the tabla from the back to the front of the stage, where he would converse so thrillingly over the long years with Chatur Lal, Kannai Dutt, Kumar Bose and, most importantly, Alla Rakha.

Ravi Shankar, the author notes, was many things to many people, "here an insider, there an outsider; here a purist, there a pioneer." But perhaps the reviewer of a 1965 concert at Town Hall, New York best captured the aura surrounding Shankar when he wrote: "Mr Shankar is a fusion of the technical wizard with the musical poet and the philosophical mystic..."

Craske's years of research has been time well spent, for Indian Sun: The Life and Times of Ravi Shankar is a feast of a read. Musically illuminating, culturally and historically insightful, the author has served Shankar's imposing legacy with an admirable mixture of compassion, scholarly integrity and candor. An important book on many levels.

< Previous

Death of a Tree

Comments

Tags

Book Review

Ravi Shankar

Ian Patterson

Faber & Faber

John Coltrane

john mclaughlin

Cab Calloway

Jimi Hendrix

Indian Sun: The Life And Music Of Ravi Shankar

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.