Home » Jazz Articles » Profile » Gilly’s Remembered

Gilly’s Remembered

Make the 50-mile trek up Interstate 75 to Gilly's in Dayton.

While the Queen City had its share of jazz spots, they mostly drew upon the local talent, which was nothing to disparage when talking about folks such as tenor saxophonist Jimmy McGary, guitarists Cal Collins, Wilbert Longmire and Kenny Poole, and pianists Ed Moss and Frank Vincent.

But to check out musicians as internationally celebrated as Charles Mingus and Sonny Rollins within an intimate club setting, you had to go to Gilly's.

My first experience there stemmed from hearing an ad spot on WNOP announcing that trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and his quartet would be appearing there.

I was not yet 21 years old, but in that era in Ohio it was legal to drink beer that was 3.2 percent or less alcohol. Most places carried what we called "low" beer, but those that did not were off-limits to minors.

At any rate, I drove my rebuilt Karmann Ghia up to the club and found a seat at a table in the back a half dozen tables or so from the entrance. I ordered a brew and surprisingly was served without questions asked.

Since it was a week night, there was not much of a crowd. Nonetheless, Freddie was fabulous, as was his band including George Cables on keyboards, Junior Cook on tenor, and Cincinnati product Ralph Penland on drums. I remember Freddie lavishing praise on his drummer after a particularly propulsive solo. This was during Hubbard's CTI era in which he had a string of hits with the albums: Red Clay, the Grammy-winning First Light, Sky Dive and Keep Your Soul Together.

From then on, I tried to make the scene at Gilly's as often as was feasible. Week after week, the club featured the brightest stars in the business.

In his recently released autobiography, Good Things Happen Slowly: A Life In and Out of Jazz, pianist Fred Hersch, a Cincinnati native, talks about seeing Sun Ra and his Intergalactic Arkestra at Gilly's. Also in an interview, Hersch recalls being in the audience when bandleader Art Pepper kicked the pianist hired for the occasion off the stand and asked if there was anyone in the audience who could sit in, an offer that Fred took up.

I caught vibes player Gary Burton with the young Pat Metheny on guitar; Dexter Gordon with Woody Shaw on trumpet and the colossal Sonny Rollins.

One of the wonderful things about live jazz in clubs, and that goes for Gilly's, is the ever-present possibility of the unexpected.

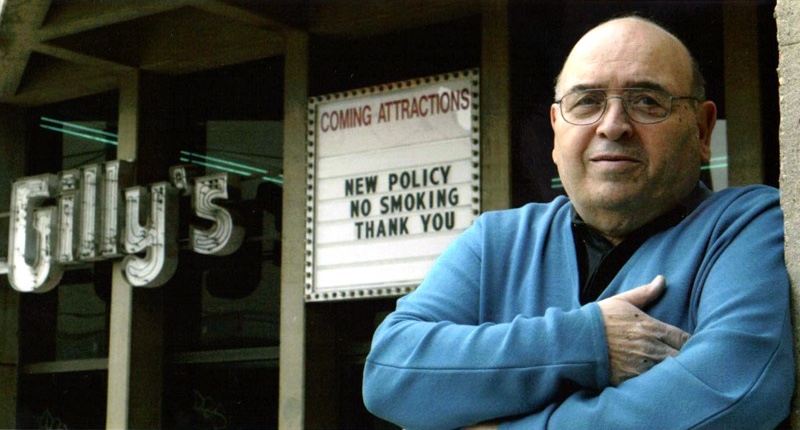

The first time I heard Mingus was at the old Gilly's, which aside from the bright sign outside, was unremarkable in appearance. It looked like your basic neighborhood bar except for the extraordinary music contained within. The site was located on the fringe of downtown, before it moved a few years later into a space within the downtown bus station.

I was ordering a drink after the first set, when imposing figure of Mingus emerged from a back room and stood by the wall, drawing on his pipe. His sensational pianist Don Pullen stood beside him and Mingus immediately began to berate him in his deep gravelly voice.

"You keep playing like that Don and I'm gonna have to fire your ass. That last song was a 12-bar Bb Minor blues and you're not playing it like that."

"Charles, you know me, I play how I play," said Pullen, who had made a reputation as a boundary-stretching outside player.

Mingus kept on grumbling while I made my way back to the table. After Mingus advanced to the stage and got behind his bass, he announced, "Ladies and gentlemen, tonight we have Eric Dolphy on saxophone, Booker Little on trumpet, Jaki Byard on piano, Danny Richmond on drums."

Laughter from the audience burgeoned. Dolphy and Little were dead and Byard long gone from the band. Only the irrepressible Richmond remained.

Along with Pullen and Richmond, trumpeter Jack Walrath and tenor sexist George Adams were in that formidable '70s Mingus band. The music that set was incandescent, as if Mingus' joke had been an incantation inculcating the spirits of the band's legendary predecessors.

The next time I saw Mingus was at the new Gilly's, which was like an airport lounge, only at the Greyhound station. The band was the same except Ricky Ford had replaced George Adams.

I noticed that behind his drum kit, Danny Richmond was wearing an especially natty suit with matching maroon jacket, slacks, tie and fedora.

When the second set was ready to begin, Richmond was absent from the bandstand. Knowing of Mingus' reputation as a taskmaster and his volatile nature, I feared something uncomfortable might happen.

After a few minutes of waiting, Mingus began tapping out a bossa on the body of his bass and the other members joined in playing the melody of the set's opening number, then launched into solos.

In walks Danny Richmond down the center aisle, now acquitted in a canary yellow suit and matching jacket, slacks, tie and fedora.

Mingus shook his head and smiled, and Richmond slid into his kit and began to cook.

Other Gilly's memories:

George Benson with keyboardist Ronnie Foster playing "On Broadway" and Benson singing "The Masquerade," before those tunes would become monster hits. Tenor saxophonist David "Fathead" Newman, he of Betty Carter and chatting with her at the bar while she drank brown liquor on the rocks and talked about her days with Lionel Hampton.

Roy Ayers ending his set by picking up the metal keys atop his vibraharp and flinging them to the floor.

I would move away from Southwest Ohio in the late 1970s and never return to Gilly's. Yet, I will never forget the great music, cultural exposure and good times I experienced there, thanks to Jerry Gillotti.

Photo credit: gillysjazz.com

< Previous

John Brackett Quartet at Redfish Rest...

Comments

Tags

Concerts

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.