Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Damien Chazelle's Netflix Show "The Eddy"

Damien Chazelle's Netflix Show "The Eddy"

Chazelle is something of a bête noire for jazz people, who’ve been highly critical of his approach to jazz. I’ve always sensed in his films an oddly ambivalence relationship to jazz, even a whiff of pathology and I needed to investigate further.

—Steve Provizer

It turns out that Chazelle directed only the first two episodes of the series The Eddy. No doubt the producers knew that by linking the program with Chazelle, a well-known and lauded filmmaker, they'd drum up more interest than by hyping the other directors Houda Benyamina, Laïla Marrakchi and Alan Poul. I don't know their work, but I do know that the cinematic style of Chazelle marks the entire production. Every episode was written or co-written by Jack Thorne and with Chazelle, their influence is enough to explain the consistent look and sound of the series.

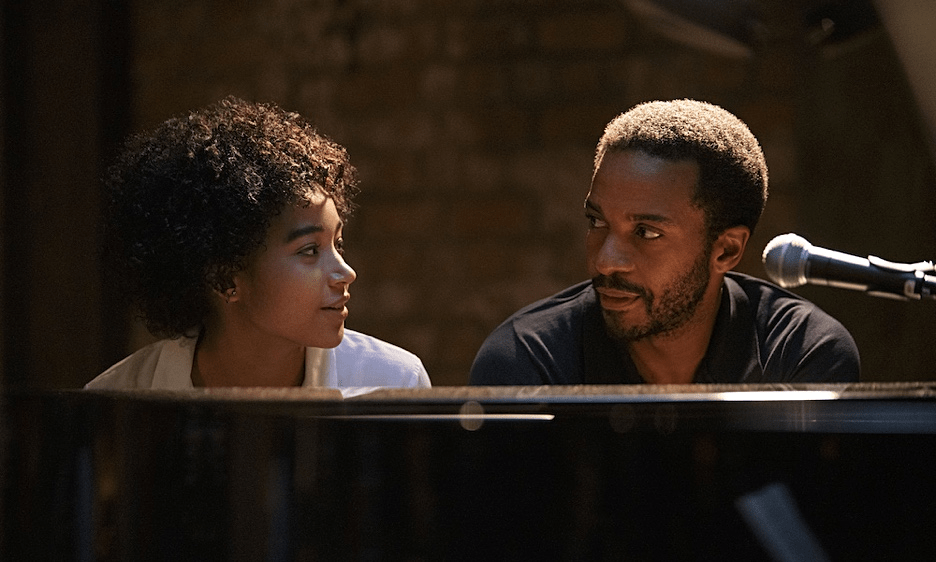

There are several cinematic techniques associated with Chazelle: highly kinetic camera movement and unusual placement, a collage approach to shooting live music and lots of extreme close-ups. Some of the directors were less active in their camera motion, but the difference was slight. All these directors put the camera in almost constant motion, sometimes swooping or sweeping, sometimes jittery. Some varied slightly from the pattern of using so many extreme close ups, but that shot was still part of the common visual language. Some directors used montages differently and some used the music played live by the band to underscore other actions and others didn't. Multiple viewings would no doubt illuminate more subtle differences, but I'm not going there and I'm not predicting how many other viewers will either. The action centers on a Parisian jazz club—The Eddy-run by ex-pat black pianist Elliot Udo, played by Andre Holland. He puts together a band for the club and surmounting various obstacles to maintain the survival of the band and of the club drives the plot. The other key players are the band's singer Maja, played by Joanna Kulig, Elliot's daughter Julie, played by Amandla Stenberg, Farid, co-owner of the club, played by Tahar Rahim and his wife Amira, played by Leïla Bekhti. One of the most positive things I can say about the show is that they managed to find musicians who could act. Lead actor Andre Holland is only called on to play sparingly and we don't have shots of his hands on the keyboard unless he's just noodling, but all the other band members are clearly professionals, actually playing their instruments or singing. This does away with the bad miming (ghosting) one sees on film. Less acting is demanded of the piano, trumpet and sax players-but the bassist (Damian Nueva) and the drummer (Lada Obradovic) have a lot to do and they do it well.

The locations are realistic, often gritty and specifically avoid the plush, romantic look of Paris we often see in films. Apart from the nightclub, action takes place on the streets of unfashionable districts, in messy apartments in high rises, amidst constructions sites and walls covered with graffiti, in a bleak hospital and an anonymous police station.

Each episode is named and focuses more on a particular character. Those characters are involved in various subplots and the filmmakers want to use this as a device to illuminate aspects of the main through-lines. Sometimes this works and sometimes giving airtime to elements that diverge too much from the key plot-drivers and characters simply breaks up the momentum.

The bad guys are Russians and they are plenty bad. We are shown that the main Russian is a jazz lover who knows the music of Elliot Udo. I guess this is supposed to add depth to this character, but for me, it fed into the oddly ambivalent attitude The Eddy takes toward jazz—more on that later.

The secondary plot concerns the struggle between Elliot and his 16-year old daughter Julie. They are both deeply wounded as, in fact, everyone is who gets any significant screen time. All the adults have deeply flawed parental figures—alcoholic, drugged, and/or abusive. Julie's stepfather attempted to molest her. Relationships are pretty well drawn, but although we're supposed to suspend judgment on a lot of selfish and withholding behavior because of everyone's wounds, I found it hard to feel deeply empathetic with the characters. I don't think the constant camera movements help, as they can be distracting in intimate moments. That said, there were some genuinely moving moments between father and daughter and some convincing emotional scenes among the others.

The language spoken in the films is probably 55% French and 40% English, 3% Russian and 2% Arabic. Subtitles pop up whenever non-English languages are being spoken; slightly confusing for a while, but you get used to it pretty quickly.

So, the music. Again, I will assume that it is Chazelle who has guided the approach. The songs, written by Glen Ballard and Randy Kerber, range from swinging music infused with funk, pop, R&B or Latin, to ballads. The compositions are good, if not challenging and the musicians are very good, technically accomplished players. There are a couple of times when the band gets freer and we hear the saxophonist move into avant-garde territory, but it's not part of the bands normal musical matrix and is not meant to stand alone, but as a kind of jagged soundtrack to dangerous and/or violent action happening outside the club.

While the trappings are hipper, there are a few scenes that are still redolent of old Hollywood musicals. One familiar trope is to use quiet piano noodling to show the hidden depths of a character. Then, there are three scenes where the singer is at the piano and effectively sight-reads a tune fresh from the pen of Cary Grant as Cole Porter; sorry—from the pen of Elliot Udo.

The most irksome aspect of the music is, in a film intent on visually representing gritty reality and in which recording live on the set is hyped, the audio quality of the music is too slick and doesn't reflect the real ambiance of the particular room in which the band is playing. The Eddy is a fairly large, cavernous-looking space, with no sound-absorbing material that I could see (For the old Bostonians among you—it reminded me of a slightly spiffier Channel). The audio may have been recorded live in that space, but what we hear on the soundtrack is the result of processing by sophisticated audio equipment. It's too good, too polished. This feels especially odd during afternoon band rehearsals. It creates a bubble within the surrounding construction of realism. In one episode, a New Orleans second line style group plays at a funeral party and—while I hope people party like that when I die—I know the sound won't be as slick and sound as great as it did on this sound track. There are two scenes with a band of young Middle Eastern kids playing hip hop with jazz elements and this music is also processed to sound more like a recording.

On the other hand, there are a few occasions when Middle-Eastern and Brazilian music are played by small groups in different locations and the director lets the music speak for itself. The audio actually reflects the real ambient room sound, without prettying it up. One such scene has the character Sami's Arabic grandmother singing in a ululating voice with guitar and dumbek and the music sounds unprocessed, raw and right.

There's another level of the film's musical approach that invites analysis: the many times that the film comments in a pejorative way on jazz. This is obliquely reflected in the smarmy, violent Russian character I alluded to before who says: "All I care about is jazz." Of course, he's evil and manipulative, but he's also a collector of jazz vinyl and proudly holds up a copy of Elliot's live recording at the Village Vanguard. Then, there's the moment when a record producer who wants to poach the band's singer is in the club talking to Elliot and says: "It's much better than the jazz I'm used to. It's, ah, boppy poppy." At another point, Sami, a smart, credible character who works for Elliot and has a romance with Julie is asked how he likes the music and he says: "It's good. They're great...But, maybe it's a little too banal." Lastly, sometimes when the band plays and there are no obvious differences with their other performances, Elliot is very critical of the playing. This is meant to impress the audience, I suppose, with the fact that Elliot has bigger "ears," and higher standards than the band, but it seems merely arbitrary and insulting to the band. All this ambivalence makes me try to parse what jazz means to Chazelle (and in this series the writer Jack Thorne). Does he love it but hate it, hate it but love it? In any case, he seems uncomfortable with it—as though it's something that's gotten under his skin that he is trying to dislodge—or to free, I suppose, depending on how you see it. One might conjecture that he thinks the audience won't sit still for anything of a lesser audio quality, but then why not process all the music? He seems more at home with the aesthetics and ethics of non-jazz music and is willing to let it speak with its own voice.

If this sounds like something that only a critic would care about, mea culpa. This level of cinematic attention to jazz is rare and The Eddy gives me more to think about than the usual jazz biopic. I concede that my prejudices make me less susceptible to the ways the filmmakers try to seduce the viewer, but Chazelle and the others have whipped up a brew of ambivalence that stimulates my curiosity, even if it doesn't satisfy my musical palate. Most viewers would probably find the character development, plot twists, visuals and music interesting enough to stick with The Eddy, although something tells me jazz-invested people may not. My own appetite is keen to see how the next episode of Chazelle's acrid romance with jazz plays out. Maybe the man will go into the woodshed and come out with a less fraught vision of the music.

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.