Home » Jazz Articles » What is Jazz? » Cold Fusion: The Search for the Jazz/Rock Unicorn, Part 2

Cold Fusion: The Search for the Jazz/Rock Unicorn, Part 2

Part 2: Steely Dan's Aja

I ended the first part of this series with the question that prompted these articles: "Why is there so little music that genuinely fuses two styles together and does so in a way that maintains the integrity of the stylistic contributors?" I could have phrased in differently by asking a closely related question: "Why is there so little fusion music that is accepted as authentic by the fans of both styles?" The answer, clearly, is that it is really difficult to maintain the integrity of both styles because compromises must be made to accommodate each, and in those compromises, the integrity of one or both is usually lost; the fans, therefore, abandon the artist's new undertaking. What is required to maintain the integrity of each style? That is where I would like to begin, because I think the answer to that question reveals why real fusion is so elusive and so rare.

I ended the first part of this series with the question that prompted these articles: "Why is there so little music that genuinely fuses two styles together and does so in a way that maintains the integrity of the stylistic contributors?" I could have phrased in differently by asking a closely related question: "Why is there so little fusion music that is accepted as authentic by the fans of both styles?" The answer, clearly, is that it is really difficult to maintain the integrity of both styles because compromises must be made to accommodate each, and in those compromises, the integrity of one or both is usually lost; the fans, therefore, abandon the artist's new undertaking. What is required to maintain the integrity of each style? That is where I would like to begin, because I think the answer to that question reveals why real fusion is so elusive and so rare. Criteria

In order to determine if stylistic integrity is intact, we first need to identify the salient features of jazz and rock, the elements of each that must, generally, be present. For jazz, there are four main elements that I think are necessary:Improvisation

The music must prominently feature improvisation. This includes improvised solos from individual members of the group, which has been a feature of jazz from the very beginning. The improvisation might be virtuosic and/or complex, or it might not be; it might be. What it must be is a unique, stylized, personal musical statement which is recognizable as such.Group Approach to Composition

The music features a group approach to both composition and improvisation. It relies on members of the ensemble to participate in the composition process by writing their own parts within appropriate stylistic parameters to enhance the overall sound. In live performances, members are expected to improvise their parts. The composition process is ongoing as it develops and morphs with each performance.Rhythmic Fluidity

While most jazz pieces maintain a consistent overall tempo, the various players in the group place themselves at slightly different parts of the beat. The drums may pull back or push ahead, while the bassist may do the opposite. The soloist may play very much "behind the beat," while the chordal accompaniment regularly vacillates between being "on top" or "behind the beat" as well. None of these rhythmic nuances can be notated because they are simply too microscopic for our notation system to handle. (For the same reasons, even if it could be notated, it would be beyond our ability to "read" anyway.) Jazz musicians play around the beat, each in different places, but the tempo remains consistent—it doesn't speed up or slow down! In this way, the music is imbued with intentional imperfections that makes it much "saucier," much more infectious, and perhaps much more "human" than music that is metronomically perfect. In the days of big band and be-bop, we called this "swing," but this rhythmic device has become so much more subtle and nuanced since then, that the term really doesn't apply in the same way to modern jazz. It's also found in the best rock music, funk, soul, and other styles, where we call it a "groove."-

Rich Harmonic Palette

While there is jazz that is triadic, using simple three-note chords, the majority of it, almost from the beginning, features a rich and colorful harmonic palette. All chords contain not only the three primary pitches (root, 3rd, and 5th) but also the 7th. Many contain 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths as well. The harmonic vocabulary of jazz is as rich as the 20C Classical music from which it borrowed so heavily.

Improvisation and Composition

Improvisation is found in rock, but it is not required. When found, it is usually short in duration, and is generally serves as a variation on a verse or chorus which provides relief from the lyrics. As in jazz, there is a strong element of "group composition," with members of the group contributing their ideas. However, unlike jazz, the expectation in the live setting is very different—rock groups do not veer far from the studio arrangements, so the compositional process ends in the studio. (Today, this is even more pronounced because most groups play with a click track that is synched to computers that run the lights and the rest of the stage show, as well as the many background tracks that accompany the bands and help to make it sound "just like the record.")Vocals

Rock music has its roots in blues and folk music, and retains the essential "story telling" aspect contained in those traditions. While instrumental rock can be found, the genre is predominantly a vocal music genre.Rhythmic Conventions in Rock

In rock and pop music, we generally expect an aggressive rhythmic approach, usually in 4/4 time, with drums, electric guitar, and bass at the core, who together lay down a strong foundational beat pattern that is accented with a great deal of syncopation, including a strong "back beat" placing emphasis on the second and fourth beat. Odd meters are rare—the genre maintains "danceable" rhythmic beat patterns that are very precise and predictable.Simple Harmony

While some rock music does rely on more colorful harmony, as a whole, it uses triadic harmony, based largely on three-note chords and relies on formulaic chord progressions.

I am highlighting my criteria largely because I know that there will be disagreement about which albums constitute a "perfect rock/jazz fusion." That disagreement is really not about the groups or the albums, it's about the criteria used to determine those groups. The last part of this series will discuss a much lesser known album and band, one decidedly more on the rock side of the spectrum.

With that as a preamble, let's get to the first of the two rare recordings that I think qualify as successful fusions of rock and jazz.

Steely Dan's Aja

In his review of Aja's 40th anniversary in 2017, Winston Cook-Wilson writes:Guitars provided auxiliary punctuation and effects-less solos rather than the brunt of the song; a stew of acoustic piano and electric keyboards, reminiscent of Miles Davis' In a Silent Way, were at the warm center of the mix. Aja's sound was a direct offshoot from jazz and fusion, steeped in its harmonic language, as well as that of turn-of-the-century modernist classical music (Debussy and Stravinsky, especially).

This is Aja in a nutshell—it features the most sophisticated jazz harmonies (which were heavily influenced by 20C classical music) that are expertly packaged in traditional pop song forms making them palatable for rock/pop fans. "Palatable" is a huge understatement—the album was enormously successful. It peaked at #3 on the Billboard charts in October 1977 and was on the charts for 60 weeks. It spawned three hit songs: "Josie," which made it to #26 and was on the charts for 11 weeks, "Deacon Blues," which made it to #19 and was on the charts for 16 weeks. It was Peg, however, that was most successful, almost cracking the Top 10 by topping the charts at #11 in March, 1978 and it also remained on the charts for 19 weeks, longer than the others. Its longevity after over four decades is remarkable; it is now an unassailable "classic" album.

Clearly Aja was popular with rock and pop music fans, easily crossing that hurdle. The recording was also a favorite with jazz musicians, whose aesthetic sensibilities require richer harmonies and more nuanced rhythmic variations than are typically found in rock/pop music. It features improvisation as a defining feature of the music, and those improvisations were performed by some of the finest jazz musicians of all time, including two ex-Miles Davis alumni, Victor Feldman and Wayne Shorter. As a fusion album, this meets all of the criteria spectacularly. It's all there—jazz harmony, vocals, improvisation, rock grooves played impeccably with jazz, soul, and funk inflections, but it's all presented with recognizable forms and tropes from the popular music idiom.

These forms and pop cliches are recognizable, but they are not the cookie cutter format that plagues so much of pop music and even jazz. In the hands of Steely Dan, with their in-depth knowledge of jazz harmony, these songs present themselves as something both familiar and new and surprising at the same time. How was this accomplished from a "nuts and bolts" musical perspective?

Fortunately, I don't have to conjecture at all—in an interview with Warren Bernhardt, Donald Fagen describes, in detail, the process of writing the song Peg. As the biggest hit from the album, the composition reveals the blending of styles on Aja that result in the perfect fusion of jazz and rock.

Steely Dan, consisting of Donald Fagen and Walter Becker (and a host of high-powered studio musicians), had already written several blues-based tunes, like "Chain Lightning" (a 12-bar blues with a few harmonic twists, similar to what Miles Davis did with "Freddie Freeloader" from the top selling jazz album of all time, Kind of Blue) and "Bodhisattva" (a jammy, jaunty 16-bar blues that has a jazz-inflected harmonic variation in the last eight measures). They continued in this direction in Peg, but took it a step or two farther. Fagen says that in Peg, they wanted to write a "major" blues that didn't have the usual blues harmony in it. So, they used the very familiar 12-bar blues structure, but avoided the typical dominant 7th chords that are used, and instead, utilized more dissonant major 7th harmonies and quartal harmony (chords stacked with intervals of a fourth between consecutive pitches), as opposed to the usual triadic harmony (chords with intervals of a third between consecutive pitches).

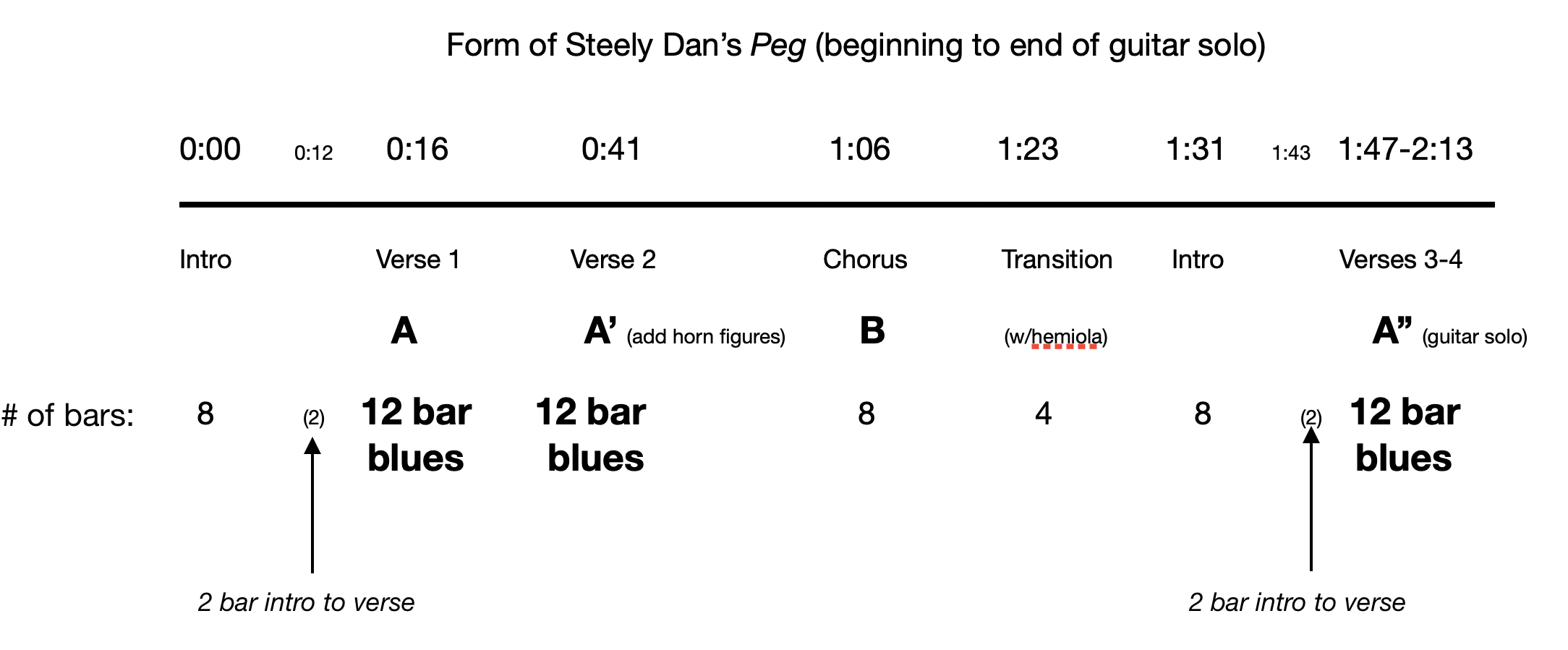

Here is the form of Peg:

[Note: For non-musicians, this graph may be confusing! Follow along and listen for the changes that take place at the specific times noted in the graph and it should be easy to understand.]

[Note: For non-musicians, this graph may be confusing! Follow along and listen for the changes that take place at the specific times noted in the graph and it should be easy to understand.] As seen in the graph, the verses in the song are a twelve bar blues that are the foundation of the tune. This is why it sounds so familiar, even upon first hearing—we've heard this progression many times before. (It's hard to believe that Peg shares the same structural DNA as Elvis Presley's "Hound Dog," or Led Zeppelin's "You Shook Me," or a thousand other jazz and rock tunes, but it does!) Yet it also sounds refreshingly different. To see how this is accomplished, let's look closely at how Fagen altered the chords in the 12-bar blues verse from how they are found in more traditional blues settings.

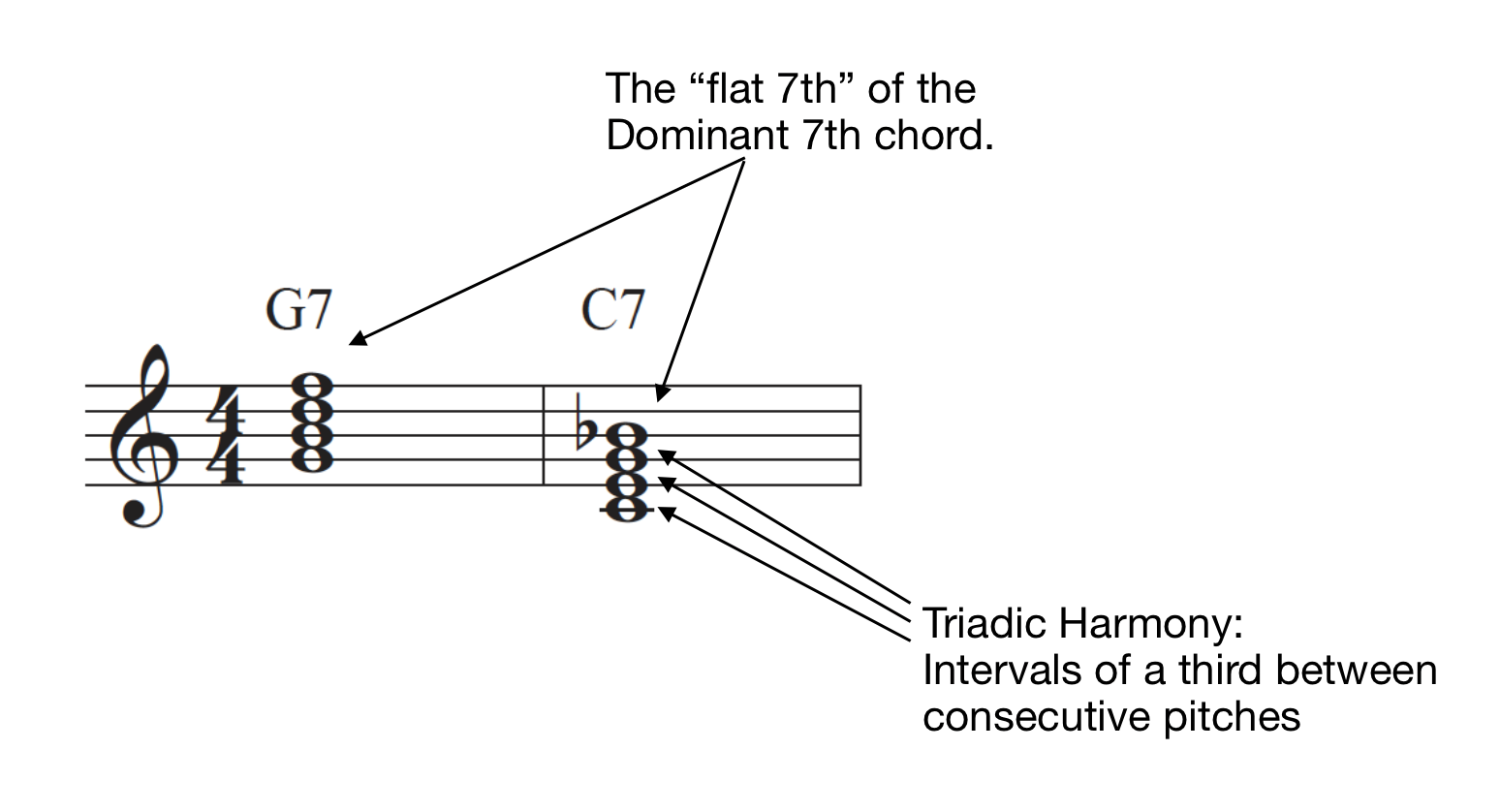

Here are the first two chords in the blues (in the key of G) with the usual triadic harmony that is found in hundreds, if not thousands, of blues tunes, including the two aforementioned songs by Elvis Presley and Led Zeppelin:

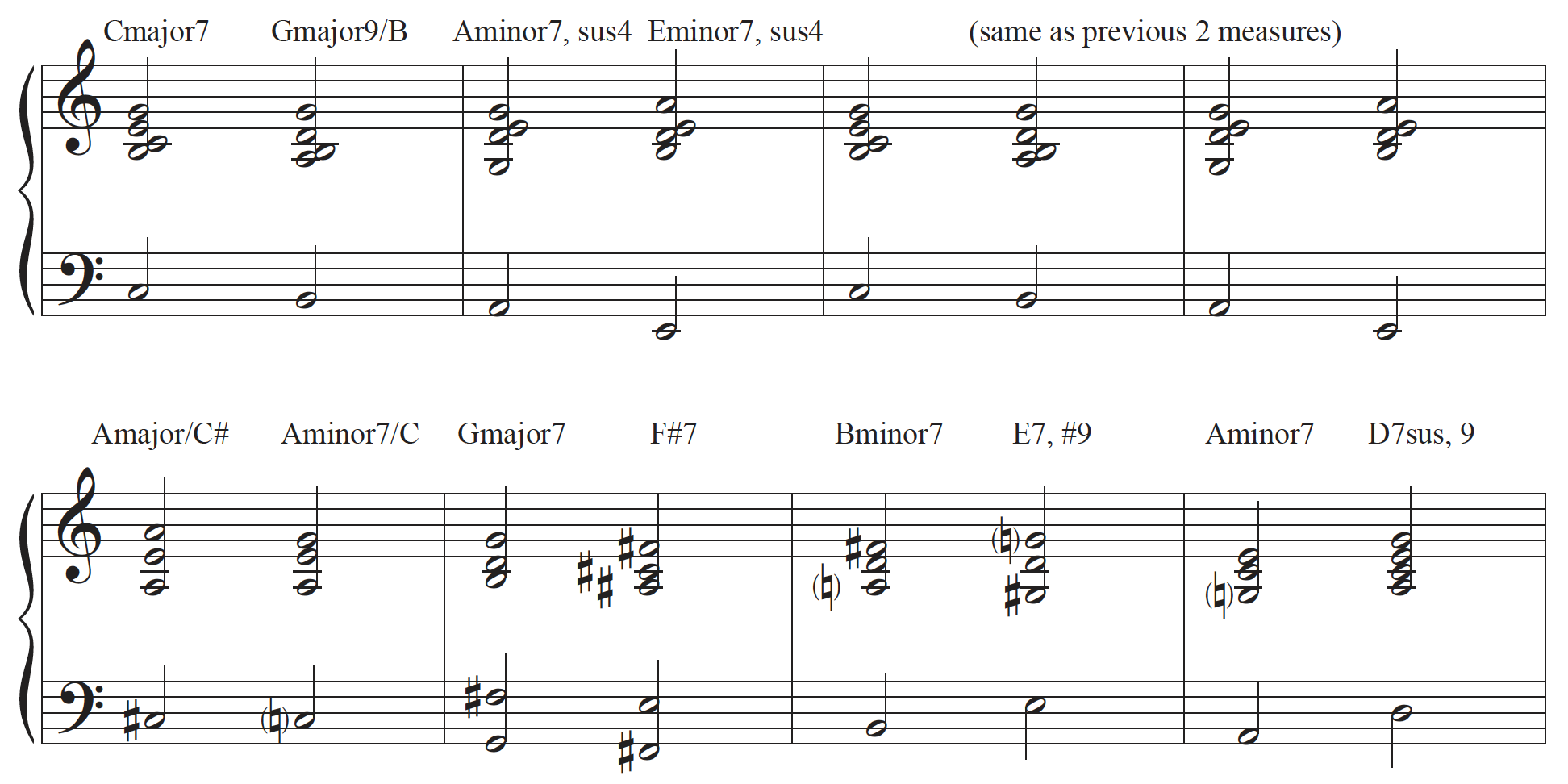

Here is the keyboard part from the first two measures of the verse in "Peg":

The differences are striking. The addition of the major 7th creates much more dissonance in the C major7 chord as does the 9th in the G major chord. In addition, the quartal harmony in the G major chords excludes the 7th entirely, which make a more "hollow" and open sound that does not have the forward motion of the dominant 7th version of the same chord in the traditional blues. These harmonies and chord voicings (arrangement and spacing of the pitches) are not common in pop music, but they are standard practice in jazz and 20C classical music. Steely Dan didn't stop there; they continued by adding even more jazz harmony in other parts of the song.

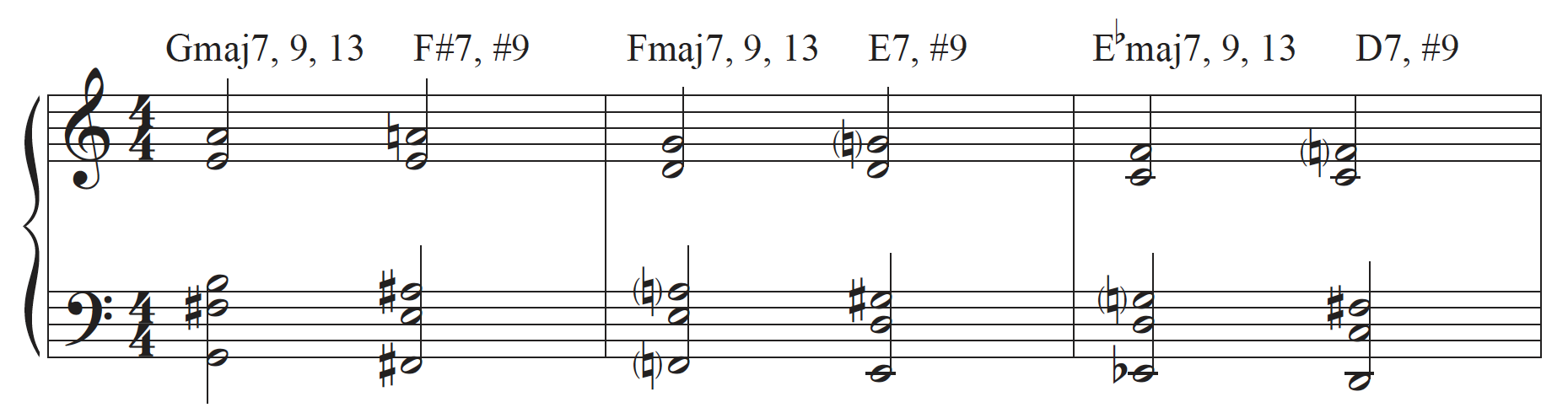

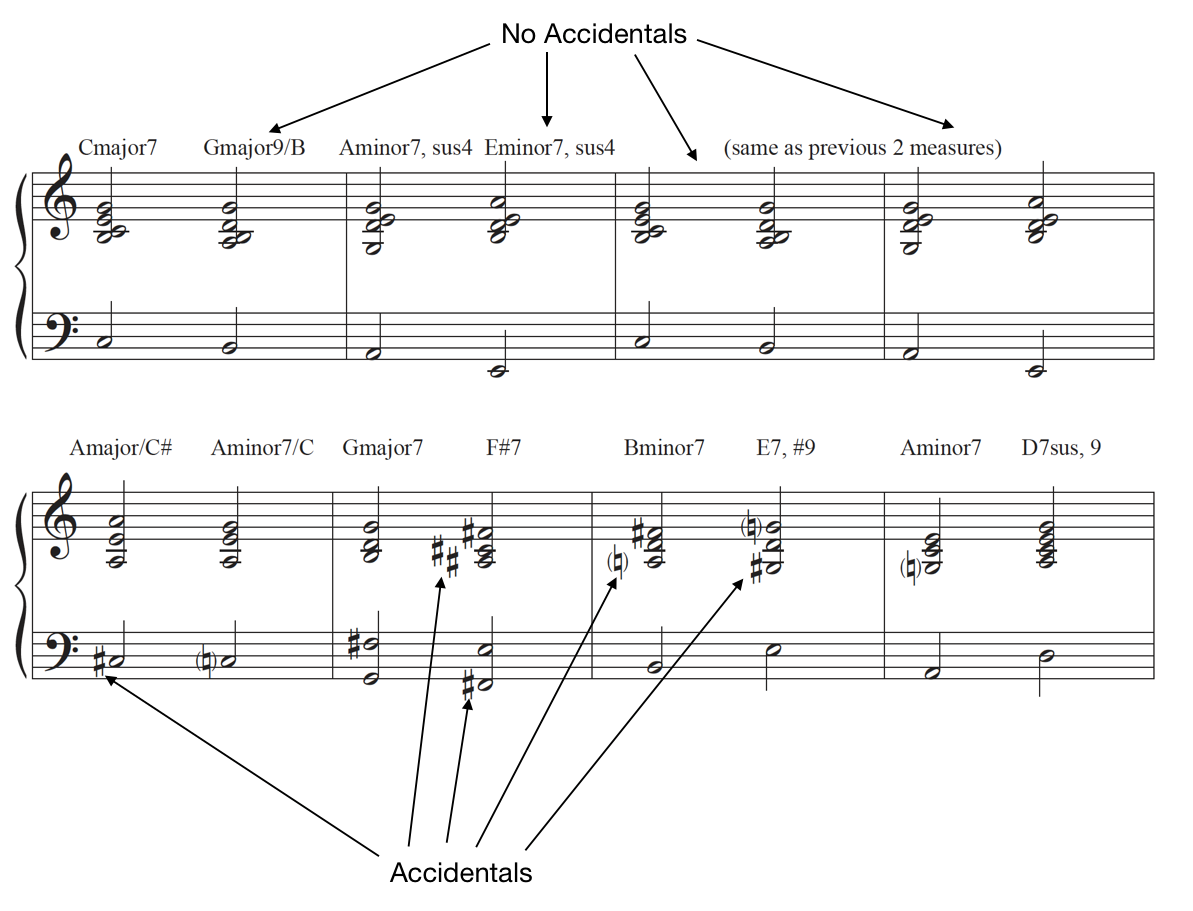

Here are the chords from the eight-measure introduction to the song:

The jazz influence from the opening salvo in the introduction is even more pronounced. All of the chords are voiced in fourths (quartal) and the dissonance level is much higher, with 9ths, 13ths, and #9s added. This is unadulterated jazz harmony—if the tune had continued with these kinds of chords, it would have been too complicated, too "jazzy" to become a major pop hit. But it did not continue like that, it moved to a modified 12-bar blues which de-escalated the provocative jazz harmony, providing a recognizable structure for the verse. What we have here is the two worlds, jazz and rock, back to back and stylistically uncompromised. The balancing of the two is exquisite—the complicated 8-bar intro, followed by a fairly simple (but still jazz inflected) 12-bar blues (repeated, for a total of 24 bars), provides the perfect blend of the two, challenging pop listener's a bit while at the same time satisfying jazz listeners, and ultimately settling in to the friendly blues-based verses. (Note the horn figures that appear for the first time in the second verse as a call and response to the vocals—in their music, Steely Dan provides regular variation like this to the listener, which highlights the jazz aesthetic at the group's core.)

After the second verse, we hear the powerful chorus, led by the unmistakable voice of Michael McDonald singing prominently in the densely packed, multi-tracked background vocals, that come roaring out of the mix like the brass section from Woody Herman's Thundering Herd. Here are the chords from the chorus:

The first four measures of the chorus are fairly simple, but do contain more quartal harmony. The bass progression is pure modal rock, and the overall effect is almost anthemic. If this were done with electric guitar instead of keyboards, it would instantly be recognizable as hard rock, but the mix of instruments here is more lush, with a rich, almost orchestral timbre. The second four measures are very different, returning to a more complicated and advanced jazz harmony. Visually, this is easily seen by the lack of accidentals in the first eight measures—it's all white notes on the piano, so there are only six different notes used, all from the C major scale. The second four measures are littered with accidentals, using 10 of the possible 12 pitches, which is something we see regularly in jazz and classical music, but not in pop. The aural result is that the first half, while quite powerful, is harmonically fairly static and bland (except for the quartal harmony), while the second half explodes with color and chromatic voice-leading that is actually a closely related variation on the chords in the introduction!** The chorus does the same thing as the intro and verse—blends the two styles in succession, only here, the rock part comes first, followed by the jazz portion to end chorus. In short, the stylistic balance demonstrated in the intro and verse is duplicated in reverse order in the chorus.

** It takes a bit of music theory work to see this relationship, which is beyond the scope of this article. I think it is, however, something that is heard, or at least felt, by listeners who intuitively recognize that these parts of the song are somehow related and as such, the introduction and the chorus are linked together, making the piece more architecturally "logical" and internally coherent.

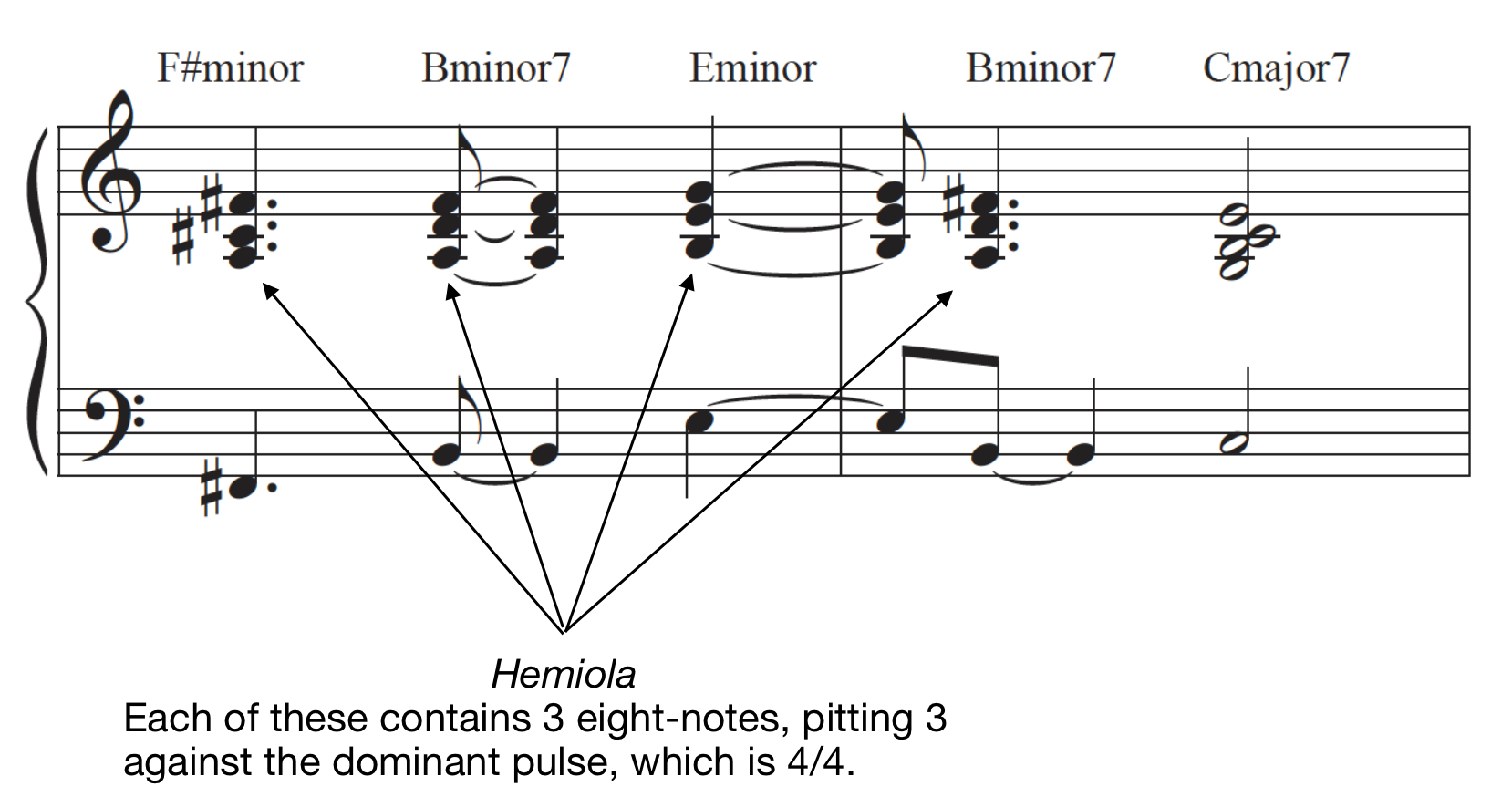

After the chorus, the tune sounds like it will return to the verse, which is the obvious choice and plays to the listener's expectations that the "verse-chorus-verse-chorus" pop format will be dutifully followed. In the hands of less adventurous musicians, it likely would have continued with the verse, but it doesn't. We hear two measures of the verse (without vocals) and then we get a strange new figure that appears for only two measures. This figure is a little jarring because the bass line moves in 4ths and it introduces the key signature of D major, which we haven't heard before. This sleight of hand is short-lived, and we quickly find out what it is leading to—the return of the introduction, not the verse! It's a clever ploy that toys with listener expectations, foiling them slightly on the way back to the familiar verse-chorus format. It's what the great musicologist Donald Tovey might have called a "purple patch"—a splash of unexpected color that surprises the listener, and in this case, makes the return to the main narrative more pleasing. The harmonic variation is not, however, the only interesting thing in this short transition—it is made more "purple" by the fact that it contains a "hemiola," which is a rhythmic device that creates accents opposed to the dominant beat pattern, usually 3:2 or 3:4. In this case, it is the latter; each chord in this transition contains three eight notes, which functions as a rhythmic dissonance to the underlying meter, almost like a brief "waltz" that shows up in a 4/4 dance. It functions in tandem with the harmony to surprise and slightly disorientate the listener, making the return to the song format more satisfying. This type of rhythmic disruption is a prominent feature in jazz, rock, and classical music.

[Note: As before, this concept may also be confusing to non-musicians. Listen for the changes that take place in the tune at 1:23 and it will easily be heard and understood.]

In this song, Steely Dan has managed to utilize a traditional form (12-bar blues) from the early 20C and cleverly merge it with the traditional verse-chorus song format (with intro, transitions, etc.), in such an organic manner that one hardly notices that the verse is a 12-bar blues. It is a stunning example of the whole being greater than the sum of the parts. Why would musicians be looking for ways of reimagining the 12 bar-blues in the first place? Well, it's a very repetitive form, with very little variation to hold our interest, so musicians have searched for ways to expand on the form just like Steely Dan did in Peg. Steely Dan, however, were not the first to do this—it has been going on from the earliest days of jazz and blues.

Consider "St Louis Blues," by Bessie Smith from 1929:

This 12-bar blues has a short introduction, then the blues form is repeated twice, followed by a contrasting 'B' section which provides relief from this very slow and languid blues. The form is thus 'AAB' form, with 'A' being the 12-bar blues.

Here's another minor variation from 1937—Count Basie's "One O'Clock Jump":

This 12-bar blues has a short introduction as well, followed by several repetitions of the 12-bar blues in the key of F with the piano featured as soloist. At 0:45, there is an abrupt change of key to the key of D-flat, and the horns take turns soloing in the new key.

Finally, compare the form of Glenn Miller's hit from the 1940s, "In the Mood," with the form of Peg:

The similarities are striking—both are based on the 12-bar blues, both were huge hits that helped to define both groups, both have eight measure introductions, both have contrasting 'B' sections as a relief from the blues, both feature improvisation, both have a four-measure transition, and both even have a two-measure intro to the verse/chorus! It's hard not to see the same musical impulses at work in both pieces. The desire to utilize the 12-bar blues is clearly there, but so is the need to reimagine it and create something new by adornment with introductions, transitions, improvisations, and other devices.

This is how Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, two jazz sons of the rock revolution, channeled the jazz of the 1940s and '50s, reinvented it, and carried it forward into the 1970s, creating a truly spectacular fusion of rock and jazz. Their earlier albums show the same approach, but on Aja the balance is both exquisite and somewhat perilous—one step further towards jazz or rock and it would have crossed the line. It seems that after the monumental musical and artistic success of Aja, there must have been the realization that they could go no further; the ultimate fusion had been achieved.

The last part of this series will discuss a much lesser known album and band, one decidedly more on the rock side of the fusion spectrum.

< Previous

McRae, Bird @ 100, Newk & More

Next >

Chunks And Chairknobs

Comments

About Steely Dan

Instrument: Band / ensemble / orchestra

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

Concerts

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.