Home » Jazz Articles » Under the Radar » Big in Japan, Part 2: Osaka & the Eri Yamamoto Connection

Big in Japan, Part 2: Osaka & the Eri Yamamoto Connection

I try to write tunes that capture a moment, whether an experience of nature or a busy city street or based on an experience on my travels.

—Eri Yamamoto

In Part 1 of Big in Japan we looked at the early history of jazz music in that country—a history that dates back to the same time frame as the Jazz Age in the United States. The influence of American dance music was indisputable but it came to Japan through second-hand means. Sheet music and early recordings were enhanced by live performances—not from American musicians—but from Filipinos who learned from the occupying forces of the U.S. Life in Japan, between the two World Wars, was in a state of flux as the country's attempt to assimilate its economy with the West coincided with weakening economies in Western Europe and the U.S. The result was not only trade barriers on Japanese products but also wide-spread anti-Asian immigration laws in the 1920s.

The internal clash of ideals was palpable: a government with growing resentment toward the West, and a populace of whom a significant segment saw the U.S. as the ideal of modern thinking. The dance music of the 1920s was emblematic of a largely mythological society that embraced individual freedom; even one that had thrown caution to the wind; it was a concept that simultaneously frightened and tempted. When it came to jazz, curiosity was winning out as dancehalls dotted some cities and thrived in others. Importantly, jazz in Japan followed the same identity strictures as in the U.S. in that the early era of music referred to as "jazz," would not technically qualify as the same jazz that later developed. From the time that jazz came to Japan, through the bebop era, the fundamental elements of the genre have run parallel to the U.S.

Osaka

Tokyo was the dominant city of the two major cultural centers in Japan at the beginning of the Jazz Age. There would have been dance band performances scheduled in many of the city's music halls and theaters on the night of Saturday, September 1, 1923. Just before noon an 8.3-magnitude earthquake—the Great Kwanto Earthquake—and the subsequent Great Tokyo Fire destroyed almost fifty-percent of the city. Hundreds of aftershocks, tornados of fire, landslides, and multiple tsunamis would claim more than one-hundred-forty-thousand lives and typhoid fever and diseases from unsanitary conditions added to a toll that was unprecedented in the records of natural disasters in Japan. International relief quickly poured in, spearheaded by the U.S. and the Red Cross, bolstering relations between the often-antagonistic world powers. Demagoguery and accusations on both sides quickly put the affiliation back in hostile territory. The process of physically rebuilding Tokyo would be years in the making. Despite the acrimony between East and West, Americanization-by-jazz not only survived but flourished, and Japan's second great cultural center—Osaka—was destined to become the country's jazz capital.Three-hundred miles to the southwest of Tokyo lies what was once called the "City of Smoke." In the late nineteenth century, Osaka lagged behind Tokyo as a commercial force in Japan and to compete with the capital, it shifted its dwindling trade-based economy for one of manufacturing. The factory smokestacks that dominated the skyline were emblematic of the city's growing workforce. As the population grew so to did slums and crime. The Yakuza, one of the largest, most persuasive and prosperous organized crime families in the world, originated in Osaka (and in Tokyo) and in the Jazz Age controlled the sale of stolen goods and the gambling business. Like their mafia counterparts in the U.S., they had strong ties to local governments and were often the money behind Osaka's jazz venues. By 1924 the city had almost two-dozen dance halls and native musicians were beginning to replace the Filipinos who had introduced live jazz performance to the country. The Dōtonbori district, the one-time dance hall center of the city was referred to as the "Japanese jazz mecca." The first stage of the Osaka jazz phenomena was short-lived. In 1927 the city's conservative ruling class—in a backlash to Americanism—delivered a decree forcing the dance halls to close. This too was a relatively brief imposition and in 1933, Chigusa, Japan's first jazz café opened.

In 1945, near the end of the Pacific theater of WWII, a U.S. bombing mission burned down Chigusa but it re-opened in the port city of Yokohama, closer to Tokyo, and it became a hangout for future stars such as pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi and trumpeter Terumasa Hino. Jazz in Osaka survived, sometimes tucked away in small neighborhoods that came through the war years with their rickety wooden buildings and tea houses intact. One such district is Nakazakicho -literally and figuratively on the other side of the Japan Railway tracks. In this seemingly misplaced neighborhood with its slight alleyways and lack of signage, one can find the club Noon directly under the elevated tracks, and Taiyo No To Café nearby. Neither club caters strictly to jazz anymore but others in the area, such as Comodo Bar and Cafe Malacca have more robust calendars. Deeper into the city, and in its Umeda business district, there is a higher concentration of jazz clubs than anywhere else in the country. Original Dixieland Jazz Club of Osaka, Meursault 2nd Club, Live BAR, Azul, Rhythm & Kushikatsu Agatta, Cafe Bourrée, New Suntory 5, Red & Blue, Bunk Johnson, Long Walk Coffee, Royal Horse, and Bēsuontoppu are among the most popular spots in the city. Like many U.S. jazz venues, some are restaurants with music, others, jazz clubs with food.

Eri Yamamoto

Osaka is considered the origin of Japanese jazz and the birthplace of dozens of nationally well-known musicians, though the majority come from the highly-manufactured ranks of J-pop—a cross between pop music and disco. Among the city's jazz artists few have a base outside the region. A notable exception is pianist and composer Eri Yamamoto. I first met the Osaka native when her trio was in the early days of their long—and ongoing—engagement at Arthur's Tavern in New York's West Village. The renowned venue has been home for the trio since 2000, originally with John Davis, and then Alan Hampton on bass. David Ambrosio has been bassist for more than ten years and drummer Ikuo Takeuchi has been with Yamamoto from the beginning. He appeared on her first trio recording Up & Coming (Jane Street Records, 2001). The remarkably stable group speaks to Yamamoto's qualities as a leader. As a collaborator, she has worked with creative music's finest talents, including William Parker, Daniel Carter, Hamid Drake and Federico Ughi. She has performed on six continents and has taught on four.Stage seating at Arthur's Tavern is literally that; a patron could inadvertently step on the drum pedal if not careful. It was the early show, the weather was bad, and patrons were slow to trickle in, none of which deterred the pianist/composer from completely immersing herself in the moment. She was clearly in her element on a stage that had once hosted legends such as Charlie Parker and Roy Hargrove. During the break in the first set, Ms. Yamamoto joined us for a brief conversation that focused on the prelude to her arrival in New York in 1995. In particular, she had a successful career teaching music in Japan, a country that reveres its educators and holds them in high esteem. Her arrival in New York and her subsequent exposure to the live jazz scene, was an instant game changer for the classically trained musician.

Yamamoto began studying piano at the age of three, later adding viola and voice to her formal training. She was composing at the age of five and later studied composition and music education at the University of Shiga. In 2017 I interviewed Ms. Yamamoto more at length and she described her early life in Japan; it is telling that the sound, silence, and the visual aspects of her world share equal footing. "I was born in Osaka, but moved to Kyoto when I was 10. So, I have more memories of Kyoto. It's a good mixture of city life, surrounded by nature. Since Kyoto was the ancient capital of Japan, there are so many temples and shrines. When I was tired of studying, of practicing, I would go to temples. They have huge gardens that are so quiet -you don't hear anything. People in Kyoto are pretty laid-back, and speak slowly, with their own sense of humor. The food is excellent, I think among the best in Japan." I asked about the transition to the New York jazz scene and she explained the whirlwind of events that changed her life so quickly and dramatically. "In 1995, when I was still living in Kyoto, I visited my sister in Manhattan, and since I was here in New York, I wanted to listen to jazz. We saw Tommy Flanagan's trio at Tavern on the Green, and I was so moved that after the set, I said to Tommy: 'I want to be like you in the future. What should I do?' He answered, 'If you want to be a jazz musician, you've got to come to New York.' The following month, I left my grad school program in composition, and moved to New York City. I was excited to be here, and I didn't have time to get scared. I was very fortunate, because the first week I found Mal Waldron's name in the Village Voice. He was playing at Sweet Basil, and he introduced me to the bassist Reggie Workman, who brought me into the New School to study jazz. While I was at the New School, I started playing a regular trio gig at the Avenue B Social Club in the East Village, and I met Matthew Shipp and several other great musicians."

Yamamoto explained how the piano—and composing—have been extensions of her life from near the beginning. Her sensory acuity again figures deeply into her love of the instrument. "I started taking piano lessons when I was three, because all of my friends were also taking lessons -in Yamaha group classes. I loved playing, as it was just 'piano and me time.' When I was eight, Osaka University of Music had a wonderful prep program, and I was the youngest. I learned sight-reading, dictation, singing, and harmony -all the foundations of music. Around that time, I started writing my own music. Around age ten, I had a wonderful teacher who was an accomplished classical pianist, and I studied with her all through high school. Early on it was all classical music, and my mom was very supportive. From the time I was eight, she bought me the best seats to see the best musicians, such as Berlin Philharmonic and Vladimir Ashkenazi (who was one of my favorite pianists and conductors.) I was so small that the seat seemed big to me, and I was surrounded by adults. I felt the vibration of the music, and also felt the excitement of live music happening in the moment."

As a trio leader, Yamamoto leans toward an animated blend of improvisation and structure, sometimes allowing Ambrosio and Takeuchi to direct the improvisational flow before jumping back in. I asked if she felt that to be an accurate description of her live trio playing and, if she has a preference for lyrical jazz or more open improvisation? Her answer is unsurprisingly Zen-like: "I love everything, regarding trio playing. I don't have an idea of how the music should sound or go, but just let it happen. I like the triangle shape, and that's what the trio is to me, three equal partners." As to adjusting to side-playing in more free-jazz oriented settings of Parker, Drake and Ughi, she responds: "I don't change anything as a player, when playing with these musicians, as my own music has a lot of open-ended tunes where we play free, not having to follow a particular form or chord progression. William, Hamid, and Federico are all lyrical musicians."

I noted that Yamamoto's AUM Fidelity albums The Next Page (2012), and Firefly (2013), seemed to be turning points in that the organic blending of her previous work now took on a unique identity of its own—music that very clearly had her own stamp on it. I asked what these two albums mean to Yamamoto as an artist. She replied that ..."for me the process of composing, playing, and recording, has been the same for many years. I try to write tunes that capture a moment, whether an experience of nature or a busy city street, or based on an experience on my travels. When Dave, Ikuo, and I play or record, we try to bring the tune to life, as a band. Maybe as the years have gone by, we've gotten a little deeper into our own sound and identity. For me that is a good feeling." Like many of her contemporaries in creative music, Yamamoto explains that genre has never defined her style: "I was studying classical music, but in Kyoto, I was surrounded by traditional Japanese music with traditional instruments. I especially liked British rock music and world music. Since coming to New York, I have appreciated such a wide variety of jazz musicians in so many styles, I can't think of genres or categories." As for the blending of traditional Japanese music and American jazz, Yamamoto had a clear picture in 2017 for a current project. "I'll always be playing trio music, but I'm also thinking about playing more solo piano, which I love to do. Also, in Shiga (where I went to college, five minutes from Kyoto), there is a traditional song that is usually sung by one singer accompanied by taiko drums. I have the idea to arrange this song for choir, so that the members of the community can sing it together, while accompanied by my trio. I can picture how the jazz beat will blend with the traditional beat of the folk song. I may very well do more of this kind of thing in the future."

That project has manifested itself as the Choral Chameleon Ensemble presentation of Yamamoto's Goshu Ondo Suite, featuring her trio and "Bon" dances -traditional in welcoming the visiting ancestral spirits. Performed in NYC on November 17 and 18, the performance was recorded and will be released at a later date. Yamamoto had previously taken a deep dive into cross-pollinating cultures with compositions that made up the soundtrack to the black and white silent movie, I Was Born, But... (1932) by Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu, whose movie Tokyo Story (1953) was voted the greatest film of all time by a panel of global directors. Yamamoto's compositions "Every Day," "A Little Escape," "I Was Born," "A Little Suspicious," "Let's Eat, Then Everything Will Be OK" from the I Was Born, But... soundtrack, also appeared on her trio release In Each Day, Something Good (AUM, 2010). The Eri Yamamoto Trio plays two sets at Arthur's Tavern every Thursday, Friday and Saturday night. The club is located at 57 Grove Street in New York City.

In the conclusion of Big in Japan we will look at the remarkable career of Tokyo avant-garde jazz pianist Satoko Fujii whose benchmark 2018 has been a monthly celebration via an unusually diverse set of releases.

Selected Eri Yamamoto Discography

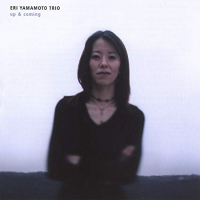

Eri Yamamoto: Up & Coming With her early trio, including John Davis on bass and drummer Ikuo Takeuchi, Up & Coming (Jane Street Records, 2001) was Eri Yamamoto's first release in the U.S. Even at this initial stage of her recording career, it was clear that the pianist had already found the means to express her unique musical views. Having recently set down roots on the New York scene, Yamamoto had been exposed to influences as diverse as Tommy Flannigan and Matthew Shipp but one can hear Andrew Hill and Bill Evans as well. All those points of reference signal the contrary point—Yamamoto's style is her own. Her straight-forward melodies are regularly toppled by surprising time changes and odd phrasing.

With her early trio, including John Davis on bass and drummer Ikuo Takeuchi, Up & Coming (Jane Street Records, 2001) was Eri Yamamoto's first release in the U.S. Even at this initial stage of her recording career, it was clear that the pianist had already found the means to express her unique musical views. Having recently set down roots on the New York scene, Yamamoto had been exposed to influences as diverse as Tommy Flannigan and Matthew Shipp but one can hear Andrew Hill and Bill Evans as well. All those points of reference signal the contrary point—Yamamoto's style is her own. Her straight-forward melodies are regularly toppled by surprising time changes and odd phrasing. Eri Yamamoto Trio: Life

Yamamoto's tenth release, Life (AUM Fidelity, 2016) reflects deep connections to her adopted home in New York. The music—new compositions and two re-workings of her older pieces—elicits a range of sentiments from cheerful enthusiasm to meditative, all with the vitality of the city. Ambrosio and Takeuchi are, by now, extensions of a unit that functions in the most symbiotic manner while leaving plenty of room for self-expression. For a trio that determinedly avoids pyrotechnics, they execute endlessly cliché-free and inventive tunes that lodge themselves in the memory.

Yamamoto's tenth release, Life (AUM Fidelity, 2016) reflects deep connections to her adopted home in New York. The music—new compositions and two re-workings of her older pieces—elicits a range of sentiments from cheerful enthusiasm to meditative, all with the vitality of the city. Ambrosio and Takeuchi are, by now, extensions of a unit that functions in the most symbiotic manner while leaving plenty of room for self-expression. For a trio that determinedly avoids pyrotechnics, they execute endlessly cliché-free and inventive tunes that lodge themselves in the memory. Eri Yamamoto: Piano Solo: Live in Benicàssim

Given Eri Yamamoto's preference for the more intimate formations of duo and trio, it is somewhat surprising that she has not recorded a solo album before Piano Solo: Live in Benicàssim (Blau Records, 2017). It was worth the wait. In live settings the pianist has been known to play solo versions of her trio compositions, as well as spontaneous improvisations and these have proven to be audience favorites. In the environs of this quaint Spanish town, Yamamoto renders brilliant melodies and subtle shadings with the expressiveness of a lyricist.

Given Eri Yamamoto's preference for the more intimate formations of duo and trio, it is somewhat surprising that she has not recorded a solo album before Piano Solo: Live in Benicàssim (Blau Records, 2017). It was worth the wait. In live settings the pianist has been known to play solo versions of her trio compositions, as well as spontaneous improvisations and these have proven to be audience favorites. In the environs of this quaint Spanish town, Yamamoto renders brilliant melodies and subtle shadings with the expressiveness of a lyricist.

< Previous

Wayne Horvitz: A Musical Portrait

Comments

Tags

Under the Radar

Karl Ackermann

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Terumasa Hino

Eri Yamamoto

John Davis

Alan Hampton

David Ambrosio

Ikuo Takeuchi

William Parker

Daniel Carter

Hamid Drake

Federico Ughi

Charlie Parker

Roy Hargrove

Tommy Flanagan

Mal Waldron

Reggie Workman

Matthew Shipp

Satoko Fujii

Andrew Hill

Bill Evans

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.