Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Joe Farnsworth: Friends In High Places

Joe Farnsworth: Friends In High Places

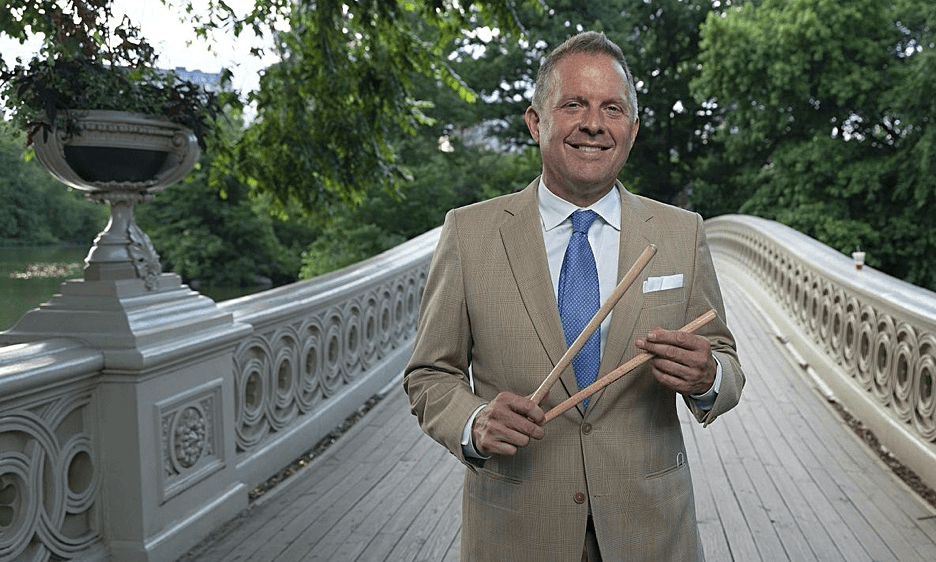

Courtesy Joe Farnsworth

COVID made a lot of time for me to think about the way I played before and the way I want to play after. I definitely want to play differently

—Joe Farnsworth

He likes to say he has friends in high places. True enough. It also helps to have monster chops and a great sense of time and swing, garnered by studying great drummers like Billy Higgins, Art Taylor, Jimmy Cobb, Max Roach and others. He's also attained his status by his own hard work and ability to absorb and retain advice from his elders. Music is also in his DNA. His father and two brother are all musicians. Brother James played saxophone with Ray Charles, among others.

With playing opportunities severely curtailed by the COVID pandemic, Farnsworth has released an impressive new recording, aptly titled Time to Swing. The superb Peter Washington on bass and piano great Kenny Barron comprise the trio cuts and the trumpet of Wynton Marsalis on four tunes makes it a quartet. As the lineup infers, the playing is great. It's in-the-pocket mainstream stuff played with elan. It has an infectious quality.

Farnsworth started playing drums as a child. Later he did gigs around his home in Massachusetts and his playing continued to rise. His important teachers include Alan Dawson and Art Taylor. Since graduating from William Paterson College in New Jersey, Farnsworth, 52, has toured incessantly, a true global road warrior. But there's more to Farnsworth than his playing ability. In the year of COVID, the drummer developed a fascinating video project that occupied many hours and is still a work in progress. It deals with music, but presents stories in a unique way. Like many musicians, he's also found more time to spend with family, in his case three sons.

Time to Swing, his fourth album as a leader (He can be found on more than 100 recordings over the years), is the project du jour, recorded on a single day in a matter of hours. That can happen when all are consummate professionals intimately familiar with straight ahead wailing.

Farnsworth is a long-time admirer of Barron and it was his first time playing with the master. "There was a record I wore out called Green Chimneys (Criss Cross, 1983) with Ben Riley. I saw him for years at Bradley's (a former well known piano bar in Manhattan)," he says. "I knew he was a genius. I just hadn't played with him before this record date. It was everything I thought and heard, but 10 times more. I actually got to interact with the guy. He couldn't have been nicer, more humble and just open to do whatever you wanted."

As for Washington, "I saw him with Art Blakey when I was in college. I've played with him a million times. He's the perfect bassist. Great guy. Loves music. We've played together in many situations. He was a no-brainer."

His respect for Marsalis goes way back. "I was in high school when Black Codes (From the Underground) (Columbia, 1985) came out. It really opened things up. I've been a big fan of his ever since then. We did a record together, it was a live thing called The House of Tribes that turned into a record. It was thrilling for me because the way he approached his playing rhythmically was similar to mine. It fit perfectly together."

To decide on the tunes, Farnsworth let Marsalis and Barron have a strong say. "I had certain tempos and feelings I wanted to play. But it was up to those guys what tunes they wanted to play... I asked Kenny, 'What's something fast you want to do?' He suggested his tune 'Lemuria,' which I had never heard before. A perfect choice. 'Star Crossed Lovers' he was warming up on at the studio. I said, 'What is that?' He forgot what he was warming up on. I said, 'Let's do it.' When you get guys like Kenny Barron, part of the graces that he brings are a wide variety of tunes. He knows way more tunes than me. He brought that in.

"With Wynton, I asked him what fast tune he wanted to play. He said 'Hesitation,' which is on his first record (Wynton Marsalis, Columbia, 1981) with Ron Carter and Tony Williams. As for a ballad, I left it up to him. What he wants to play is more meaningful than what I want to play. He came up with 'Darn That Dream.'"

"For Mr. Cobb" was something Farnsworth decided to do to honor the drum great who died earlier this year. It's a drum solo. "I was thinking about, 'What if I was in one of those drum battles. Live at Newport with Max Roach and Roy Haynes. Then Joe Farnsworth. (chuckles) What are you going to do? You have to have a melodic theme, then build off it, then bring it back. I thought about Jimmy Cobb so much. He was on my mind. I did something not particularly what he would do, but something inspired by him."

Recalling Cobb, Farnsworth said he was once contacted by a drummer from overseas seeking a drum lesson. "It dawned on me, 'Why would you want to take a lesson with me when Jimmy Cobb is here (in New York)?' So I would call Jimmy and say, 'I'm bringing a lesson to you.' Then I would call the lesson guy and I'd say, 'Let's take one with Jimmy.' They would say, 'I can't believe it.' So we'd go over to Smoke nightclub and have a lesson. So it was win-win for me, because I put money in Jimmy's pocket, and I got to sit there and get a free lesson from Jimmy Cobb (chuckles)."

Cobb "meant the world to me, man. He raised the level in New York City, that's for sure. I used to see him with the Nat Adderley group in New York City. That was one of the best groups I've ever seen, with Larry Willis and Walter Booker. It was a great time. Jimmy made the whole group. I've never heard a drummer fill up the room with that much swing. The sound was incredible."

Farnsworth says the songs were mostly done in one take, with the exception of maybe one, which only took a pair of takes. "Kenny Barron was all one take. Peter Washington suggested doing 'Time Was' again. He wanted to play a different feel on it. The Kenny Barron part was done in, like, an hour and 45 minutes. Then we waited for Wynton to come in. He's all business. He got the trumpet out. We played the blues one take, then he went into 'Hesitation.' That was one take. 'Darn That Dream' was one take. 'Down by the Riverside,' one take. Four hours. Those tunes in less than three hours is pretty good.

"The thing about Kenny Barron. You know he's playing the right changes. You just know it. He knows the songs and you know he's going to play it great. I was so confident. You play with a lot of piano players, and they're very good. But there's a lot of nebulous changes going with youngsters. Like, 'Oooh. That didn't sound right.' Especially after you've played with Harold Mabern for 30 years. You know what changes are right and what changes are wrong. That's exactly how I felt. You knew Kenny Barron knew what was going on."

There were no gigs planned to support of the CD. Not because of COVID, but because each of his mates are in such demand that there wouldn't have been time to make schedule. "I just wanted to document playing with Wynton, because we played 20 years ago. I've been having that feeling for a long time and I was just waiting for the right time to get that feeling I had 20 years ago. Just put it out in a present mode."

Cranking out good music was the priority. For Farnsworth, that has always been a priority.

His father was a music teacher in the Midwest. (He still teaches). The family moved to Massachusetts, where Joe was born. Eventually in the household, there was brother John's room, who played trombone, and James' room, who played saxophone. His brother David was a drummer and that was young Joe's room as well.

James was keen on doing sax transcriptions, especially Sonny Rollins and Sonny Stitt and the album they recorded with Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Side Up (Verve, 1959). Influences from the sax side of things could be gleaned from that room. The next door down, the trombone player John's influences of J.J. Johnson, Curtis Fuller and others could be absorbed. "So I had a little 52nd street right in my little town of South Hadley (Massachusetts). I would go up room to room, listening. Because my father was a teacher, we had a million records. It was jazz from the start."

As for his drum playing brother, things got more real. "He had a beautiful drum set. He would get up and go to school. This was before I was in kindergarten. He'd say, 'Don't touch my drums' and point at me. I'd watch him walk to school and once I couldn't see him anymore, I would pound on the drums. My father had a 10-foot-tall amplifier. I don't know why he had it, but it was right next to the drums. I had a tape deck. I would tape a record, and put this tape blasting through the amp. I played all day long with Buddy Rich and Sonny Payne."

As early as fifth grade, he started playing small gigs in one of his brother's jazz bands around South Hadley. When he was in eighth grade, the family moved to Jakarta for a time. They would stop in Japan, where jazz is popular and certain recordings could be found there that were not available in America. One shopping trip produced Miles Davis Live In Tokyo. Farnsworth was expecting electronics, more like Weather Report, which he was into at the time.

"That's what my eighth grade brain was thinking," he says. "But that record changed my life. There was Tony Williams on drums. I had never heard that before. I say, 'Holy cow.' That got me from big bands into small groups. Then you read the liner notes and it's a whole journey in itself. I studied up on Tony Williams and Miles Davis. I found out Tony Williams studied with Alan Dawson. He was from Boston. So I started taking lessons from Alan Dawson for three years. I was a freshman, sophomore, junior in high school. My father would drive me out to Boston. We were about an hour and 15 minutes away. We'd drive out once every two weeks."

He also met Charles 'Majeed' Greenlee, a trombone player from Detroit who had played with Dizzy Gillespie and had moved to Springfield, Mass. He imparted a lot of knowledge on the brothers Farnsworth.

At William Paterson College, Mabern and Cedar Walton were on the staff. They would become important in Farnsworth's life. Upon graduating, his first taste of the big time was a European tour with singer Jon Hendricks. But the first huge step followed when he was hired by Benny Golson, a job that lasted some eight years. Bassist Dwayne Burno, a friend in a high place, was instrumental in procuring that gig.

Now familiar with Mabern, Farnsworth appeared constantly in the audience at his gigs. "Because of that, he got me a gig with George Coleman, who I still play with. With Benny Golson, we did a big tour. That got me with Curtis Fuller and Art Farmer. Cedar Walton was another one. Billy Higgins passed away, then Kenny Washington did it. With Cedar, when I was in college, there were only two camps of music—the Cedar Walton group and the George Coleman group. Those were the two people I had my eyes on that I wanted to play with."

Like with Mabern, he followed Walton, gig to gig. "Every time he looked up, he saw my face," Farnsworth said. When Washington left the drum chair in the trio, Farnsworth was hired "because he knew I knew the music. Because I showed up at every gig. Bradley's, Sweet Basil's, the Vanguard. Non-stop."

Washington also helped him get a gig with Diana Krall that lasted two years. "We were so busy, then we had a week off. That week, what a blessing. George Coleman called. He said Harold Mabern needs a drummer. So I went down to the Jazz Standard and I ended up playing with him for 16 years."

A gig with McCoy Tyner came about because of bassist Gerald Cannon. "Once again, I had some friends in high places. I'm very lucky and grateful," Farnsworth says.

It's been jazz full tilt for Farnsworth. Important gigs. Important recordings. He still thanks his teachers Dawson and Taylor, as well as other heroes like Higgins, Haynes and Roach. He also roomed for a time with Jimmy Lovelace, a bebop drummer who played with people like Wes Montgomery, George Benson and Junior Mance. "We played a lot of drums together, practiced together. He was one of the great drummers; not so famous, but underground. But that was the way he liked it."

In early 2020, Farnsworth was playing at the Village Vanguard in New York City when things were shut down because of COVID.

First, Farnsworth turned to family, having to deal with the schooling of his three sons. Amid that, with time on his hands, he got an idea.

"I started making videos of some of the great masters that I knew and what they said to me and what I learned from them. I'm still doing it. I had so much fun."

On some videos, he visits sites that are important in jazz. He tells stories and re-tells some he was told, providing colorful verbal and visual imagery.

"I did one on Billy Higgins. That was 10 or 15 minutes long. Two weeks later it was Harold Mabern's birthday, so I did a whole thing on him. I started going out more. Harold Mabern loved Birdland. He played there a bunch. I went to the original Birdland. It's been a strip club for many years. I stood outside there (to film). Then I went outside Slug's where Lee Morgan was shot. I'd never been down there. It was interesting to go back in time. That was, like, an hour because I knew Harold so well. Then I did something on Max Roach.

"Cecil Payne used to live with me. He and Max grew up together in Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. I'd never been to Bed-Stuy, so I did a big thing on Max and where he grew up. It was thrilling. I loved it. Now I'm in the midst of Roy Haynes."

COVID has actually helped this project because both Farnsworth and people he tried to reach are available. "I was able to talk to guys I was never able to talk to. Steve Gadd. Chick Corea. Roy McCurdy. Ron Carter. These guys are usually on the road. But now I had a chance to talk to them. And they made videos for me."

Beyond local musicians, Farnsworth also has delved into a global video project he is excited about, an offshoot of the CD title, Time to Swing.

"I have people talking about how swing connects us all. Not everyone hates everybody," he says, referring to the social and political climate. "There are people who don't like each other out there. But music connects us all. I have people making videos from every part of the world. Indonesia, Syria, Paris, New York. Now I'm putting it all together."

The videos will be found on a YouTube site called Joe Farnsworth Presents. There are already some videos on the site.

"It's taken so long. I want to make it almost like a travel show... The video part is the easiest. Its putting them all together and editing that takes time. I would say the New York City part and the United States part should be done soon. I got a lot of people in New York City. George Coleman, Louis Hayes, Cecile McLorin Salvant.

He says its not just for musicians, but fans and just people interested in different things.

"It shows you different parts. We have a Native American out in New Mexico. He's talking about what swing means to him and you can see a bit of New Mexico. I wanted the people to go outside and show the area they're at. One guy's outside the Eiffel Tower. One guy's at the Coliseum in Rome. So you can see it. I'm thrilled with it. It goes deep into history," he says. "There's a blind drummer from Syria. I cant believe I'm talking to someone from Syria. I've never been there. Or someone in Lebanon. I don't even know what he's playing. He's outside showing a little bit of Beirut."

Meanwhile, like all musicians, Farnsworth awaits the time when things will loosen up and gigs will return. He has already done a few record dates.

"COVID slowed everything down, but I have to say I kind of liked it because it's been nice to slow my life down, my thoughts down, and interact with people. I see more people now than before. People are more isolated now, but I haven't been that way. I've reached out and spoken to people. I used to be, 'Let's call him later. He's probably cool.' But now I reach out and talk to them," he says.

Farnsworth was still playing with Mabern in 2019. The pianist died in September of that year.

"That was a lot of my life, trying to get him work and book him. No one was helping us at all. It was all me doing it. I put a lot of time into that. When he passed away, I had to do something with all that time and energy... I needed to grow up, man. I was always focused on playing with someone else. Cedar Walton or Pharoah or Harold. It was easier for me to prepare myself to support a great person. The pressure would be on the leader. After Harold passed away, just trying to grow up and try to be some sort of—I hate to say leader—but at some point you've got to. I'm 52. You've got to pass on what you know to the other guys. Some never saw Art Taylor or Art Blakey or Elvin Jones or Billy Higgins."

He's also happy about spending time with family. "My youngest son plays a ton of baseball. I've been able to take him to every single game and watch every single inning. Take care of them. That's great," says Farnsworth. "I'm practicing. Trying to change the way I play. Be different. Trying to use more space. COVID made a lot of time for me to think about the way I played before and the way I want to play after. I definitely want to play differently, for sure."

"I'm staying very busy. Not running and gunning on gigs, but definitely occupied."

Comments

Tags

Interview

Joe Farnsworth

R.J. DeLuke

United States

wynton marsalis

Diana Krall

McCoy Tyner

George Coleman

Pharoah Sanders

Eric Alexander

benny golson

Billy Higgins

Art Taylor

Jimmy Cobb

Max Roach

Ray Charles

Peter Washington

Kenny Barron} comprise the trio cuts and the trumpet of {{Marsalis

Alan Dawson

Art Blakey

Ron Carter

Tony Williams

Roy Haynes

Sonny Rollins

Sonny Stitt

J.J. Johnson

Curtis Fuller

Buddy Rich

Sonny Payne

Cedar Walton

Jon Hendricks

Bennie Golson

Dwane Burno

George Coleman

Art Farmer

Kenny Washington

Dianna Krall

Wes Montgomery

george benson

Junior Mance

Steve Gadd

Chick Corea

Roy McCurdy

Louis Hayes

Cecile McLorin Salvant

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.